Pembelajaran Mesin (Machine Learning)

Translation of Machine Learning for Everyone in Indonesian.

Mengapa kita ingin mesin bisa belajar?

Ini Paijo. Paijo ingin membeli mobil. Paijo mencoba menghitung berapa rupiah yang harusi dia tabung per bulan untuk bisa membeli mobil. Paijo lalu bertanya kepada temannya, juga mencari informasi di internet: ternyata harga mobil baru berkisar Rp.200 juta, kalau mobil second usia setahunan jatuh di Rp.190 juta, yang usia dua tahunan jatuh di Rp.180 juta dan seterusnya.

Paijo, sang calon pemilik mobil yang cerdas ini, menemukan polanya: jadi, harga mobil itu tergantung dari usianya, dan diperkirakan turun Rp.10 juta per tahun. Tetapi harganya tak akan lebih rendah dari Rp.100 juta.

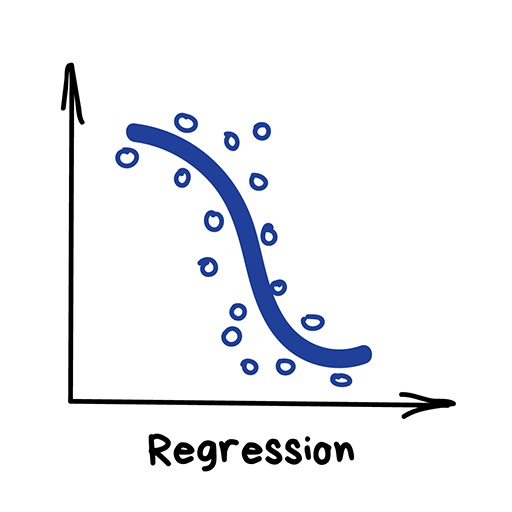

Dalam istilah pembelajara mesin, Paijo menemukan apa yang disebut regresi–bahwa dia bisa memperkirakan sebuah nilai (harga) berdasarkan data yang diketahui. Banyak orang yang terbiasa melakukan ini, misalnya saat membeli smartphone bekas (second), atau saat belanja beras untuk kepentingan kenduri (apakah per orang dijatah satu atau dua ons beras?).

Seandainya saja kita punya rumus sederhana untuk setiap hal di dunia tentu saja semua akan terasa mudah. Kita tak perlu pusing memperkirakan, atau bertanya, atau menawar. Tetapi sayangnya, hal tersebut tak mungkin.

Kembali ke urusan mobil yang mau dibeli Paijo. Masalahnya adalah saat membeli mobil, Paijo (dan kita juga) akan berhadapan dengan berbagai ragam perincian yang menentukan harga mobil: bulan dan tahun produksi, ragam variasi interior dan eksterior, kondisi mobil, jumlah kilometer, waktu pembelian (karena saat mendekati lebaran biasanya harga naik), dan lain sebagainya. Pada umumnya, kita dan Paijo tak mungkin mengingat dan memperhitungkan semua faktor harga tadi untuk menentukan tawaran harga mobil yang akan diajukan.

Nah karena kita manusia itu malas dan bodoh - apalaig urusannya matematika -, maka kita butuh mesin atau robot untuk membantu kita memperhitungkan harga buat kita, entah harga mobil, harga tanah, atau harga saham. Jadi, kita perkerjakan mesin untuk menghitung itu semua atau bahkan memperkirakan harganya. Maka, kita sediakan sejumlah data kepada si mesin, lalu meminta si mesin untuk mencari pola yang terkait dan menentukan harga sesuatu.

Dan, ternyata bisa. Hal yang paling menyenangkan adalah ternyata terbukti mesin bisa bekerja menghitung dan memperkirakan secara lebih baik daripada kebanyakan orang.

Itulah yang menjadi asal muasal lahirnya pembelajaran mesin (machine learning).

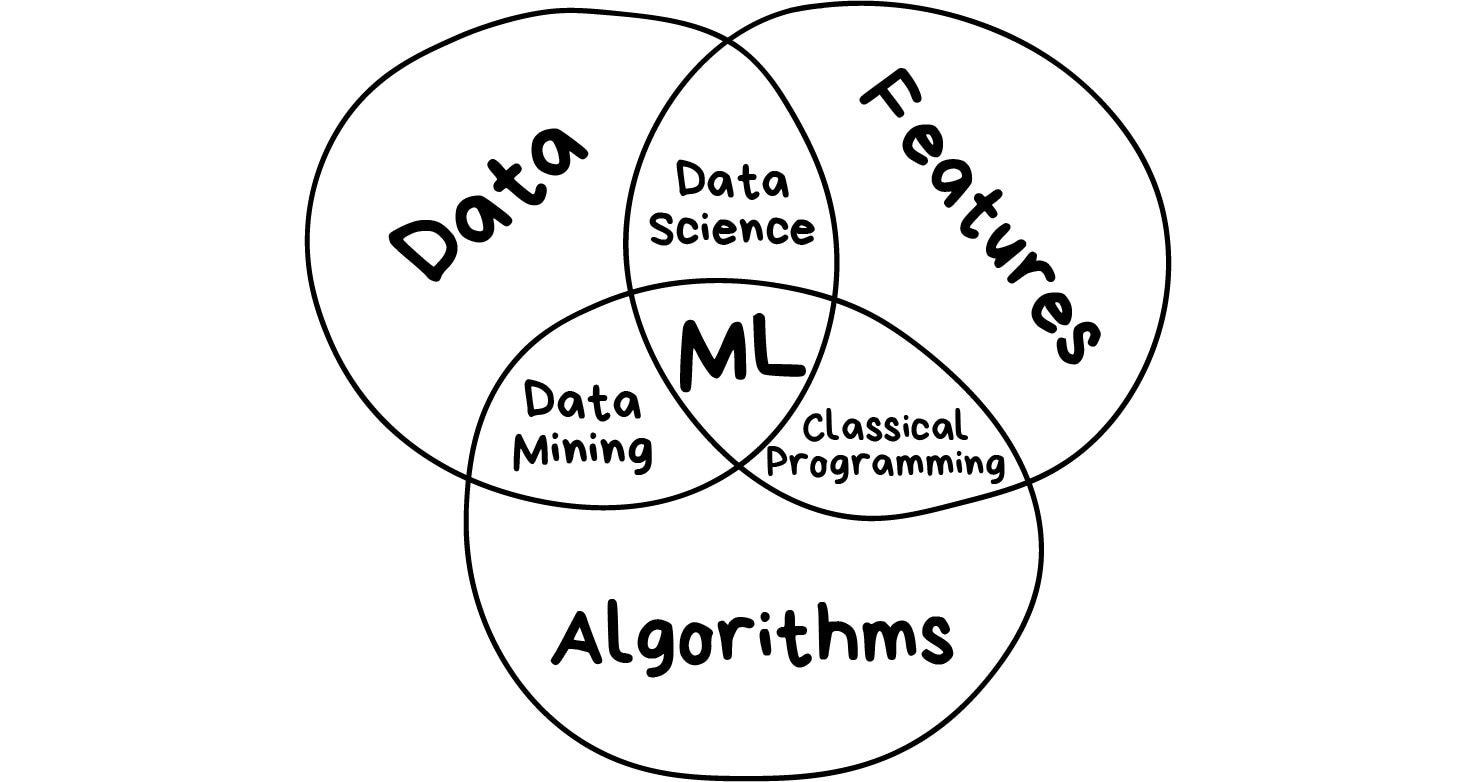

Tiga Komponen Pembelajaran Mesin

Tujuan sebenarnya dari pembelajaran mesin adalah untuk memprediksi hasil berdasarkan data yang disediakan. Semua pekerjaan pembelajaran mesin harus dapat dinyatakan dengan cara seperti ini. Kalau tidak seperti itu berarti sejak awal itu bukan merupakan pekerjaan dari pembelajaran mesin.

Semakin banyak variasi dari sampel yang kita punya, maka akan menjadi lebih mudah bagi mesin untuk mencari pola yang relevan dan memperkirakan hasilnya. Oleh karena itu, kita membutuhkan 3 komponen untuk mengajar mesin untuk bisa belajar.

Data

Kita ingin mesin mendeteksi spam? Maka carilah pesan atau email yang berisi spam. Kita ingin mesin bisa meramalkan harga saham? Maka carilah data harga saham sebanyak-banyaknya. Kita ingin mencari pola pengguna internet? Maka kumpulkan data aktivitas mereka di Facebook (eh Mark Zuckerberg, jangan terus mengumpulkan data kita terus dong!). Semakin banyak variasi dari data kita maka semakin baik hasil peramalannya. Sebagai patokan, puluhan ribu baris data adalah syarat minimum bagi yang menginginkan peramalan yang baik.

Maka ada dua cara utama untuk mendapatkan data: manual dan otomatis. Data yang dikumpulkan secara manual akan memiliki kesalahan yang lebih sedikit akan tetapi akan membutuhkan waktu yang lebih banyak untuk mengumpulkannya sehingga membuat biayanya secara umum lebih mahal.

Pengumpulan data secara otomatis itu secara umum lebih murah, yaitu kita cukup mengumpulkan segala apapun yang kamu dapat kita temukan dan berharap itu data yang kita kumpulkan itu adalah yang terbaik.

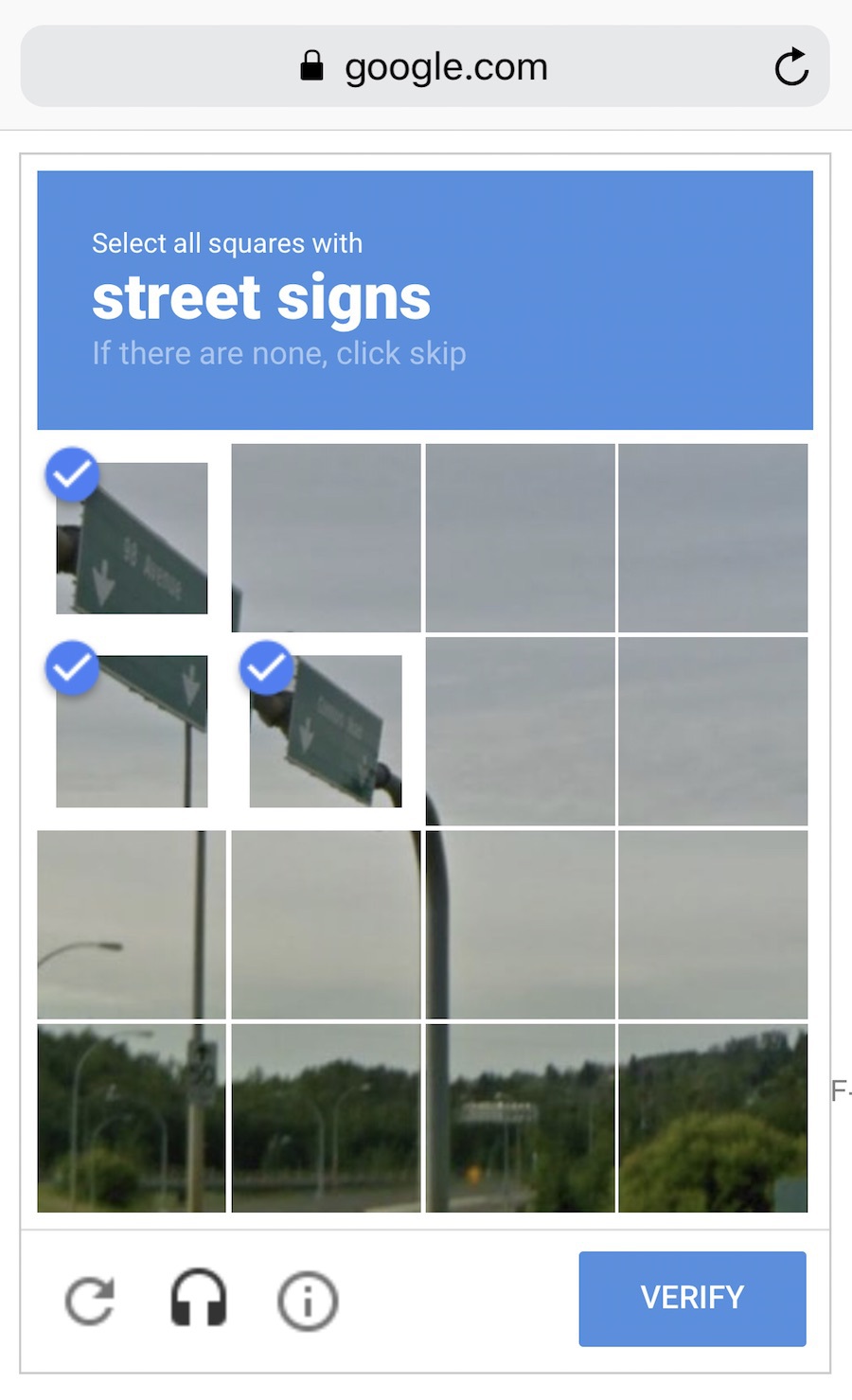

Orang pintar seperti misalnya yang bekerja di Google bisa memberdayakan konsumen mereka sendiri untuk memberikan label data bagi mereka secara gratis. Anda ingat ‘ReCaptcha’? Itu loh yang kadang memaksa kita untuk memilih mana gambar lampu lalu lintas, mana gambar mobil dll.? Nah, itulah adalah yang mereka lakukan pada kita. Kita menjadi buruh yang gratis! Keren kan?

Pada dasarnya untuk mengumpulkan data yang bagus (biasanya disebut sebagai dataset) itu sangat sulit. Maka mudah kita pahami, mengapa kita lebih banyak menemukan algoritme atau kode program untuk pembelajaran mesin, tetapi jarang menemukan dataset-nya..

Fitur

Atau dikenal juga dengan istilah parameter atau variabel. Fitur dapat berbentuk jenis kelamin pengguna, harga saham, atau frekuensi kata di dalam sebuah teks. Dengan kata lain, fitur adalah faktor-faktor yang perlu dilihat dan diperhatikan oleh mesin.

Saat data disimpan dalam tabel, fitur dapat dengan mudah diletakkan sebagai nama kolom. Akan tetapi, bagaimana jika kita memiliki koleksi dataset gambar kucing sebesar 100 GB? Kita tidak dapat secara sembrono menggunakan setiap pixel sebagai sebuah fitur. Itu mengapa memilih fitur yang tepat biasanya membutuhkan waktu yang lebih panjang daripada semua waktu yang dibutuhkan dalam berbagai tahapan dari pembelajaran mesin. Hal tersebut juga merupakan sumber kesalahan yang paling utama. Manusia itu selalu subjektif, mereka memilih fitur-fitur yang mereka sukai atau yang mereka anggap penting.

Algoritme

Ini adalah bagian yang paling jelas. Setiap masalah dapat diselesaikan dengan cara yang berbeda. Metode yang kita pilih akan berdampak kepada presisi, unjuk kerja, dan ukuran dari model (algoritme) yang akhirnya kita pakai. Akan tetapi ada ada hal yang penting untuk diperhatikan: jika data kita itu jelek, maka algoritme yang terbaik sekalipun tidak akan menolong. Hal itu disebut sebagai "sampah yang masuk - sampah yang keluar" (garbage in - garbage out). Jadi jangan terlalu memberikan perhatian yang yang terlalu besar kepada persentase akurasi, akan tetapi usahakan untuk mendapatkan data yang lebih banyak terlebih dahulu.

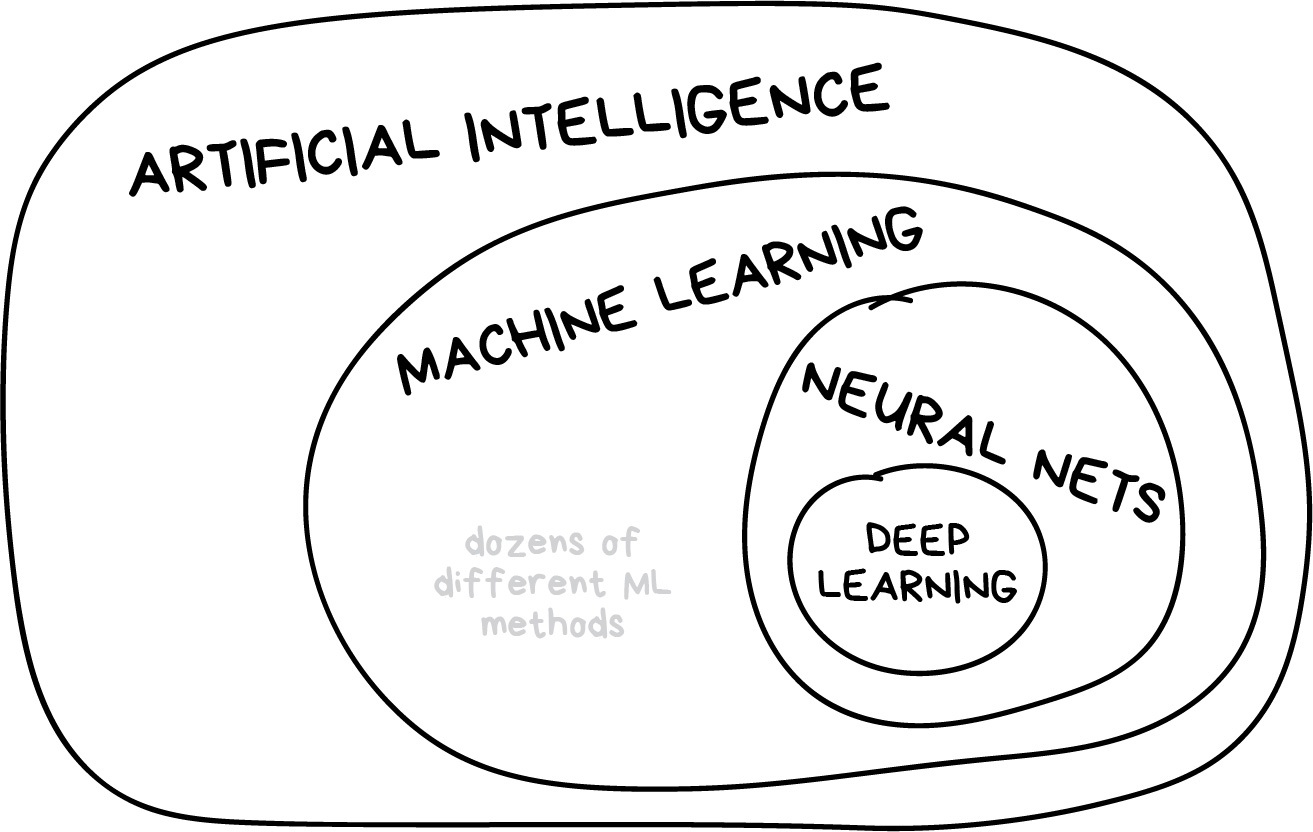

Once I saw an article titled "Will neural networks replace machine learning?" on some hipster media website. These media guys always call any shitty linear regression at least artificial intelligence, almost SkyNet. Here is a simple picture to show who is who.

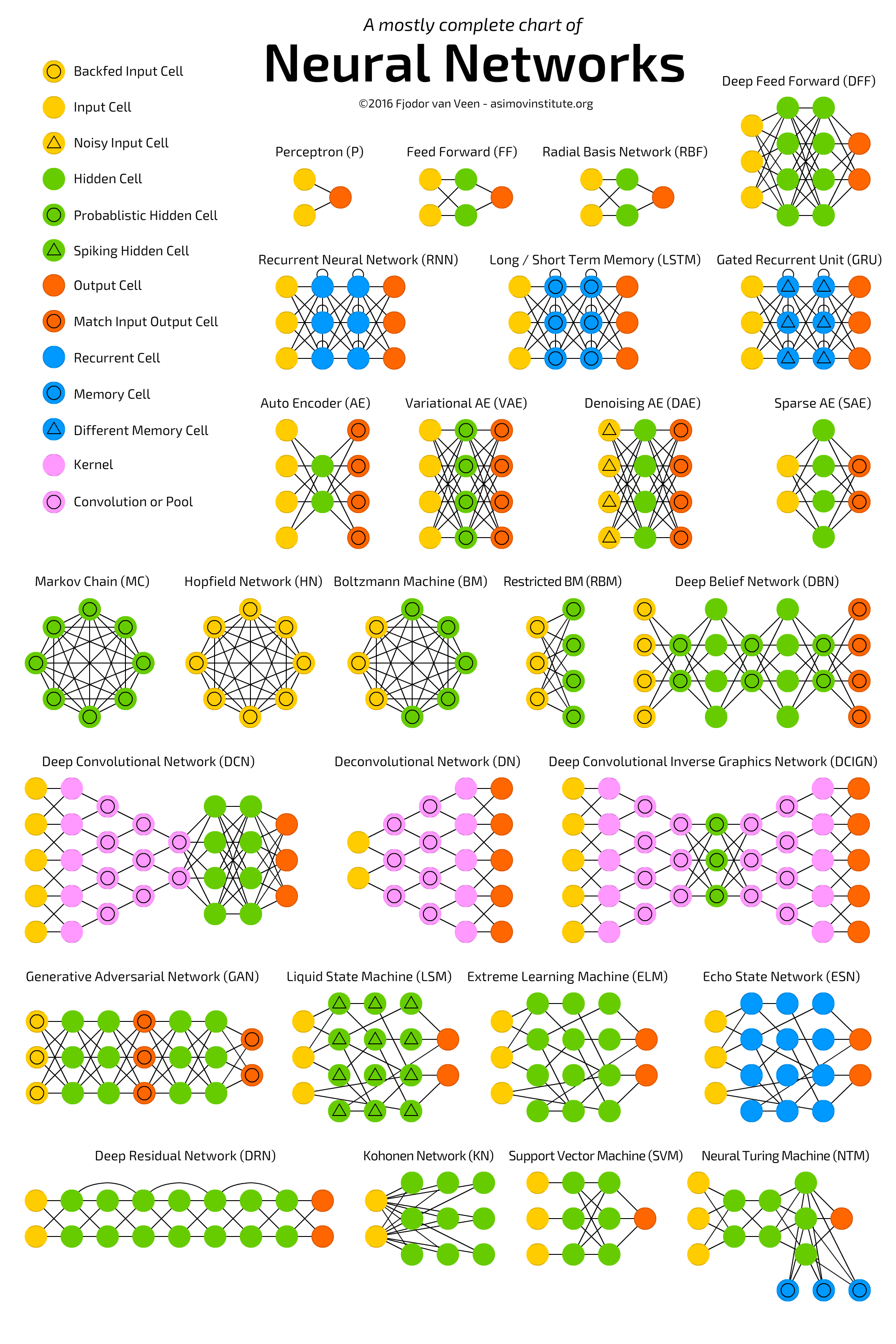

Artificial intelligence is the name of a whole knowledge field, similar to biology or chemistry.

Machine Learning is a part of artificial intelligence. An important part, but not the only one.

Neural Networks are one of machine learning types. A popular one, but there are other good guys in the class.

Deep Learning is a modern method of building, training, and using neural networks. Basically, it's a new architecture. Nowadays in practice, no one separates deep learning from the "ordinary networks". We even use the same libraries for them. To not look like a dumbass, it's better just name the type of network and avoid buzzwords.

The general rule is to compare things on the same level. That's why the phrase "will neural nets replace machine learning" sounds like "will the wheels replace cars". Dear media, it's compromising your reputation a lot.

Machine can

Machine cannot

Forecast

Create something new

Memorize

Get smart really fast

Reproduce

Go beyond their task

Choose best item

Kill all humans

If you are too lazy for long reads, take a look at the picture below to get some understanding.

Always important to remember—there is never a sole way to solve a problem in the machine learning world. There are always several algorithms that fit, and you have to choose which one fits better. Everything can be solved with a neural network, of course, but who will pay for all these GeForces?

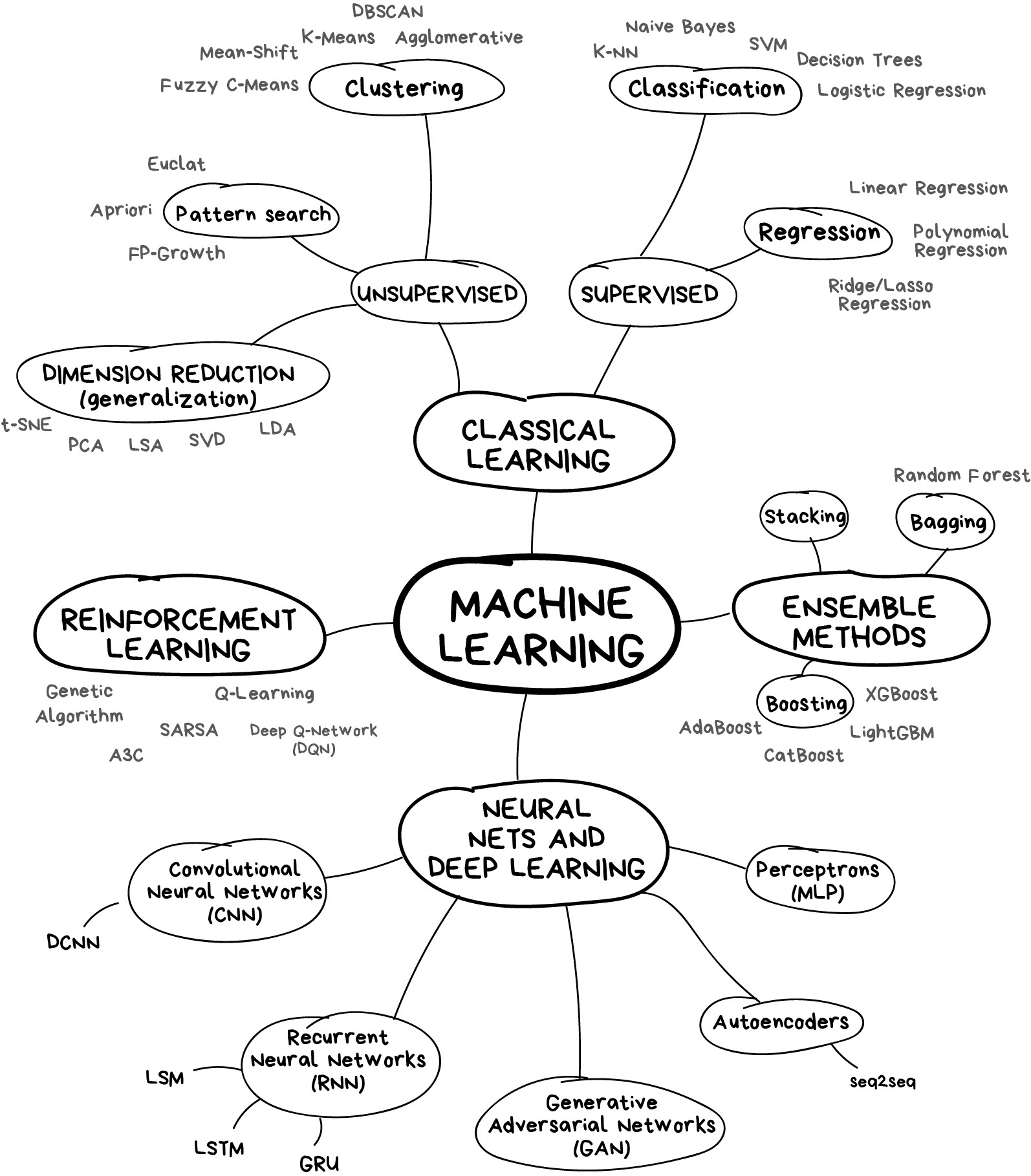

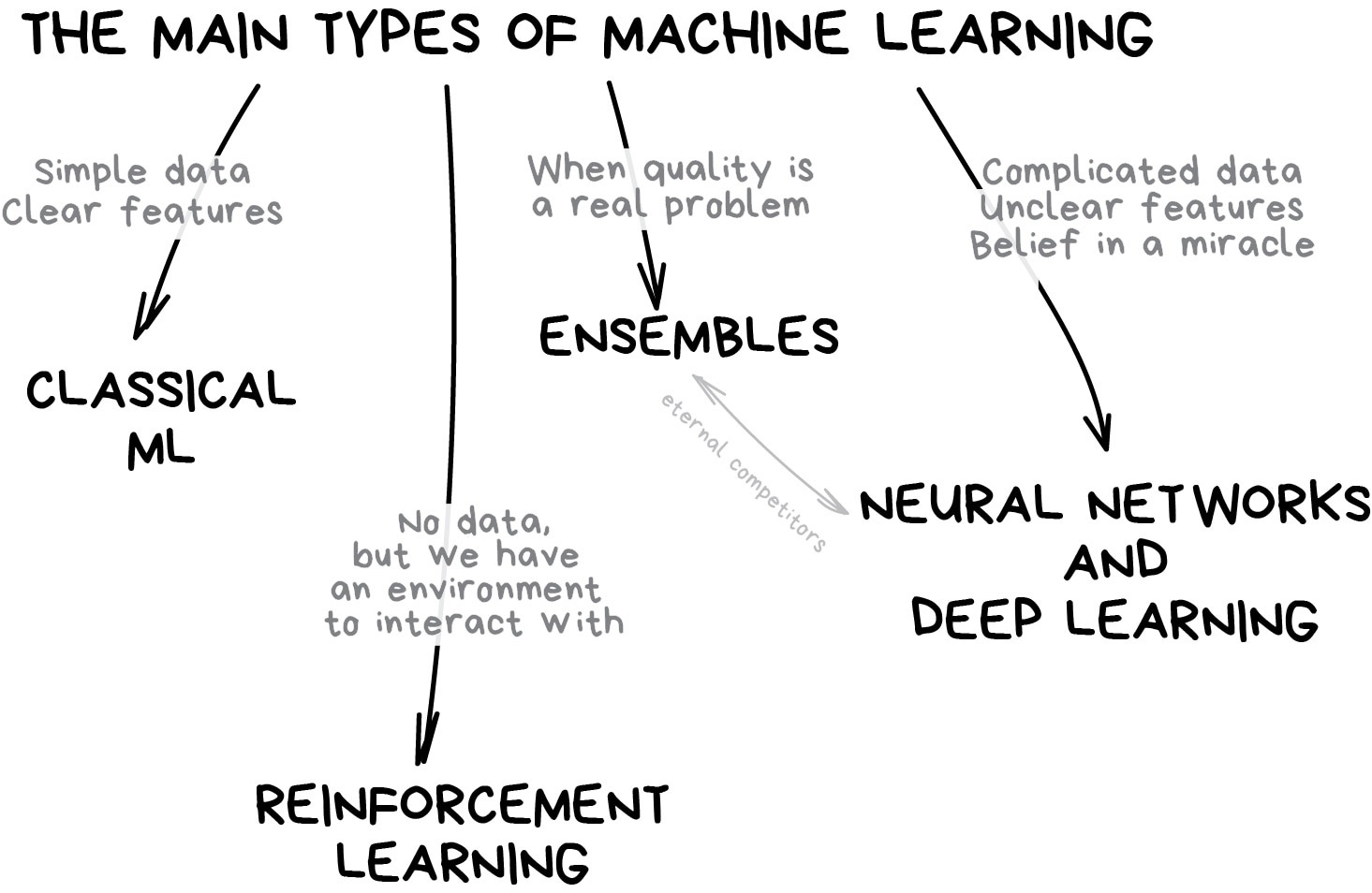

Let's start with a basic overview. Nowadays there are four main directions in machine learning.

The first methods came from pure statistics in the '50s. They solved formal math tasks—searching for patterns in numbers, evaluating the proximity of data points, and calculating vectors' directions.

Nowadays, half of the Internet is working on these algorithms. When you see a list of articles to "read next" or your bank blocks your card at random gas station in the middle of nowhere, most likely it's the work of one of those little guys.

Big tech companies are huge fans of neural networks. Obviously. For them, 2% accuracy is an additional 2 billion in revenue. But when you are small, it doesn't make sense. I heard stories of the teams spending a year on a new recommendation algorithm for their e-commerce website, before discovering that 99% of traffic came from search engines. Their algorithms were useless. Most users didn't even open the main page.

Despite the popularity, classical approaches are so natural that you could easily explain them to a toddler. They are like basic arithmetic—we use it every day, without even thinking.

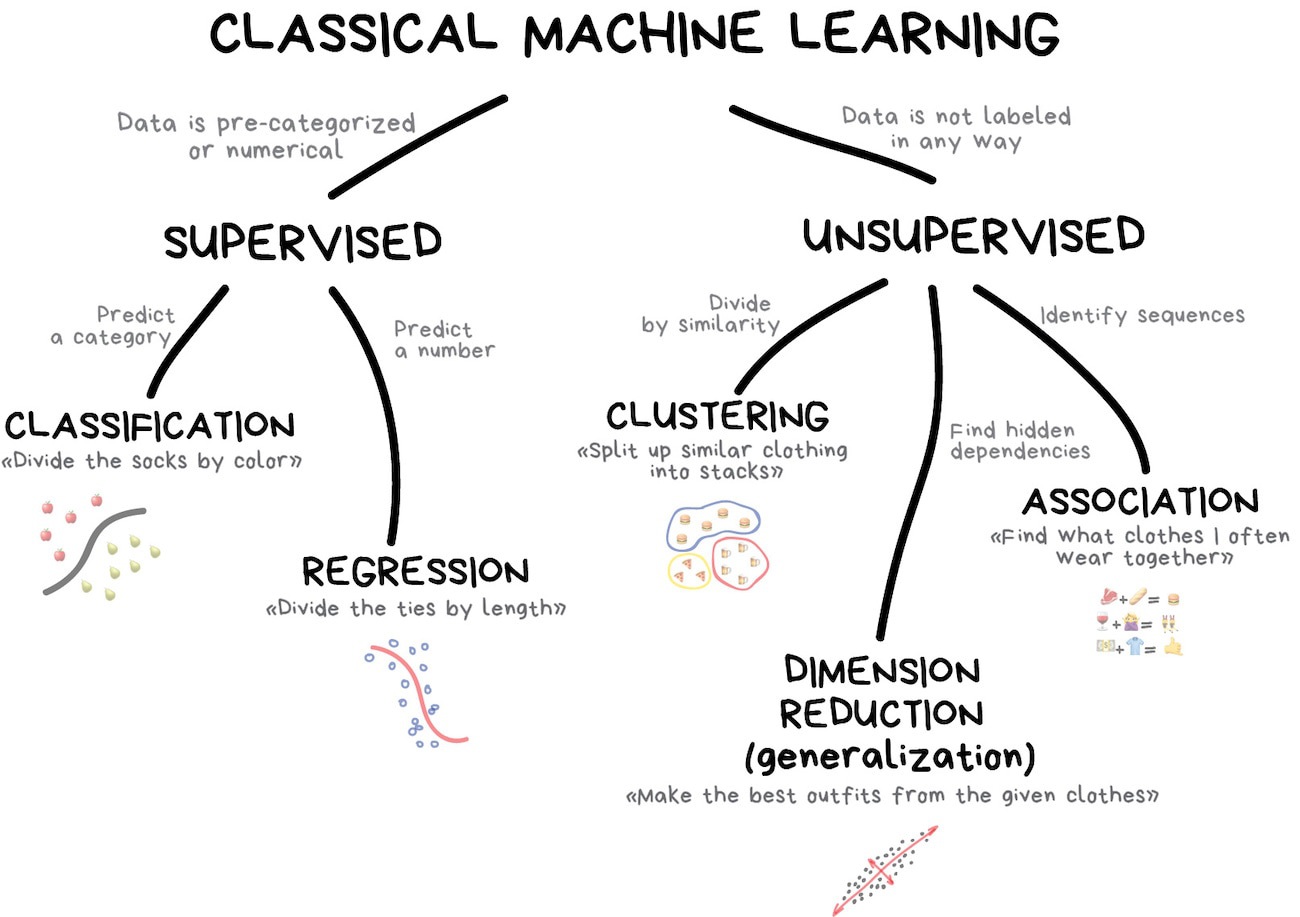

Classical machine learning is often divided into two categories–Supervised and Unsupervised Learning.

In the first case, the machine has a "supervisor" or a "teacher" who gives the machine all the answers, like whether it's a cat in the picture or a dog. The teacher has already divided (labeled) the data into cats and dogs, and the machine is using these examples to learn. One by one. Dog by cat.

Unsupervised learning means the machine is left on its own with a pile of animal photos and a task to find out who's who. Data is not labeled, there's no teacher, the machine is trying to find any patterns on its own. We'll talk about these methods below.

Clearly, the machine will learn faster with a teacher, so it's more commonly used in real-life tasks. There are two types of such tasks: classification–an object's category prediction, and regression–prediction of a specific point on a numeric axis.

"Splits objects based at one of the attributes known beforehand. Separate socks by based on color, documents based on language, music by genre"

Today used for:

–Spam filtering

–Language detection

–A search of similar documents

–Sentiment analysis

–Recognition of handwritten characters and numbers

–Fraud detection

Popular algorithms: Naive Bayes, Decision Tree, Logistic Regression, K-Nearest Neighbours, Support Vector Machine

From here onward you can comment with additional information for these sections. Feel free to write your examples of tasks. Everything is written here based on my own subjective experience.

Machine learning is about classifying things, mostly. The machine here is like a baby learning to sort toys: here's a robot, here's a car, here's a robo-car… Oh, wait. Error! Error!

In classification, you always need a teacher. The data should be labeled with features so the machine could assign the classes based on them. Everything could be classified—users based on interests (as algorithmic feeds do), articles based on language and topic (that's important for search engines), music based on genre (Spotify playlists), and even your emails.

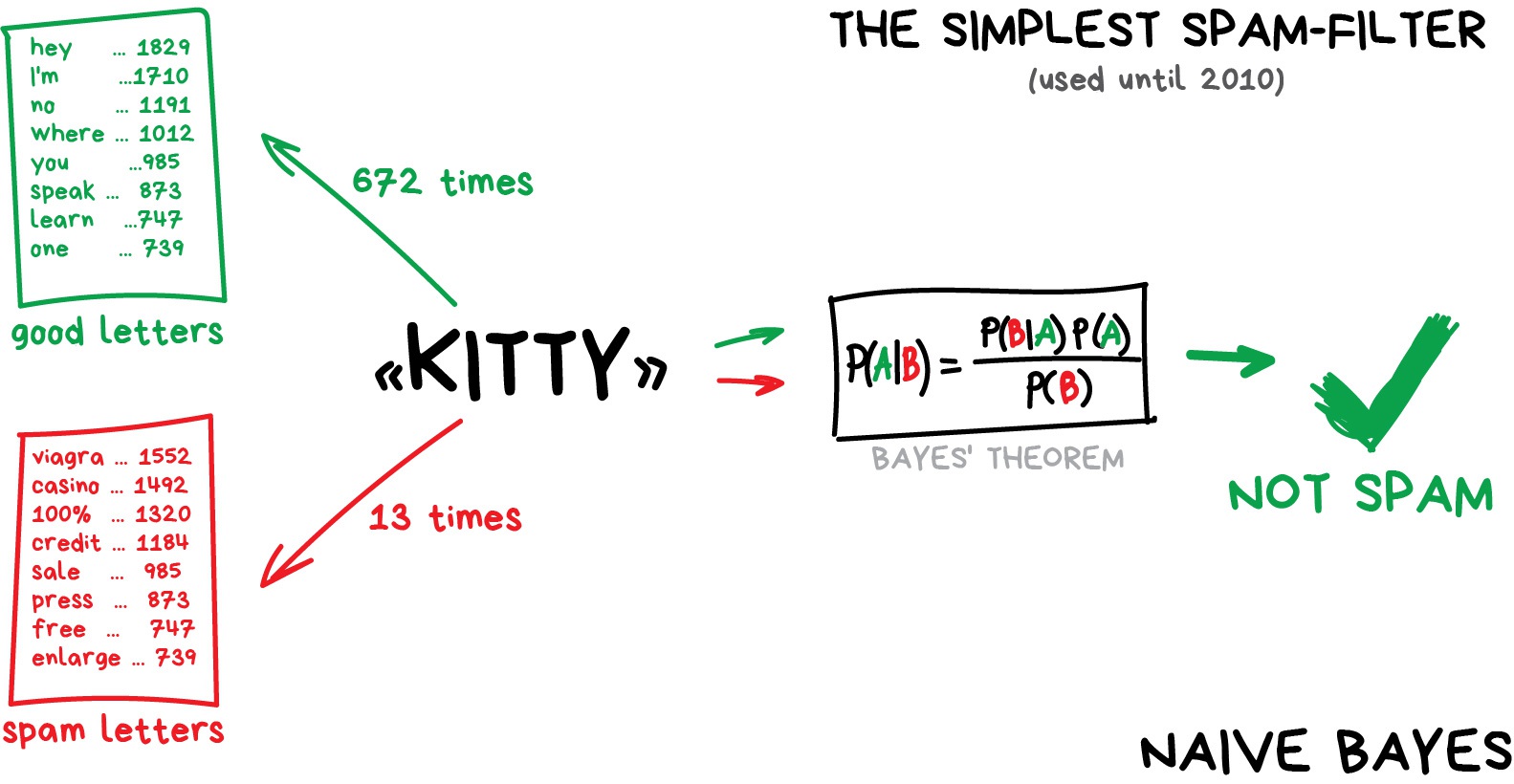

In spam filtering the Naive Bayes algorithm was widely used. The machine counts the number of "viagra" mentions in spam and normal mail, then it multiplies both probabilities using the Bayes equation, sums the results and yay, we have Machine Learning.

Later, spammers learned how to deal with Bayesian filters by adding lots of "good" words at the end of the email. Ironically, the method was called Bayesian poisoning. Naive Bayes went down in history as the most elegant and first practically useful one, but now other algorithms are used for spam filtering.

Here's another practical example of classification. Let's say you need some money on credit. How will the bank know if you'll pay it back or not? There's no way to know for sure. But the bank has lots of profiles of people who took money before. They have data about age, education, occupation and salary and–most importantly–the fact of paying the money back. Or not.

Using this data, we can teach the machine to find the patterns and get the answer. There's no issue with getting an answer. The issue is that the bank can't blindly trust the machine answer. What if there's a system failure, hacker attack or a quick fix from a drunk senior.

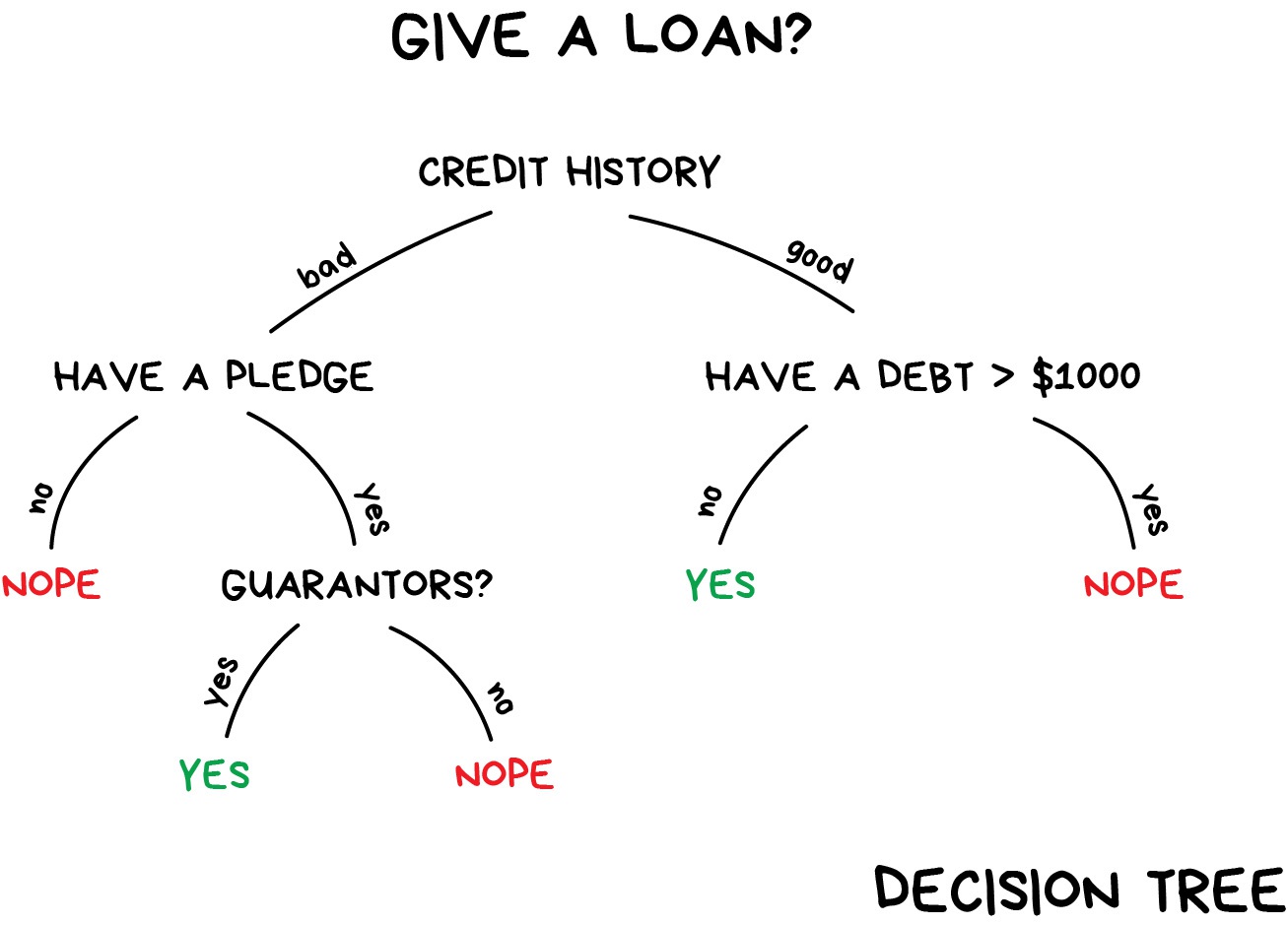

To deal with it, we have Decision Trees. All the data automatically divided to yes/no questions. They could sound a bit weird from a human perspective, e.g., whether the creditor earns more than $128.12? Though, the machine comes up with such questions to split the data best at each step.

That's how a tree is made. The higher the branch—the broader the question. Any analyst can take it and explain afterward. He may not understand it, but explain easily! (typical analyst)

Decision trees are widely used in high responsibility spheres: diagnostics, medicine, and finances.

The two most popular algorithms for forming the trees are https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Predictive_analytics#Classification_and_regression_trees_.28CART.29 and C4.5.

Pure decision trees are rarely used today. However, they often set the basis for large systems, and their ensembles even work better than neural networks. We'll talk about that later.

When you google something, that's precisely the bunch of dumb trees which are looking for a range of answers for you. Search engines love them because they're fast.

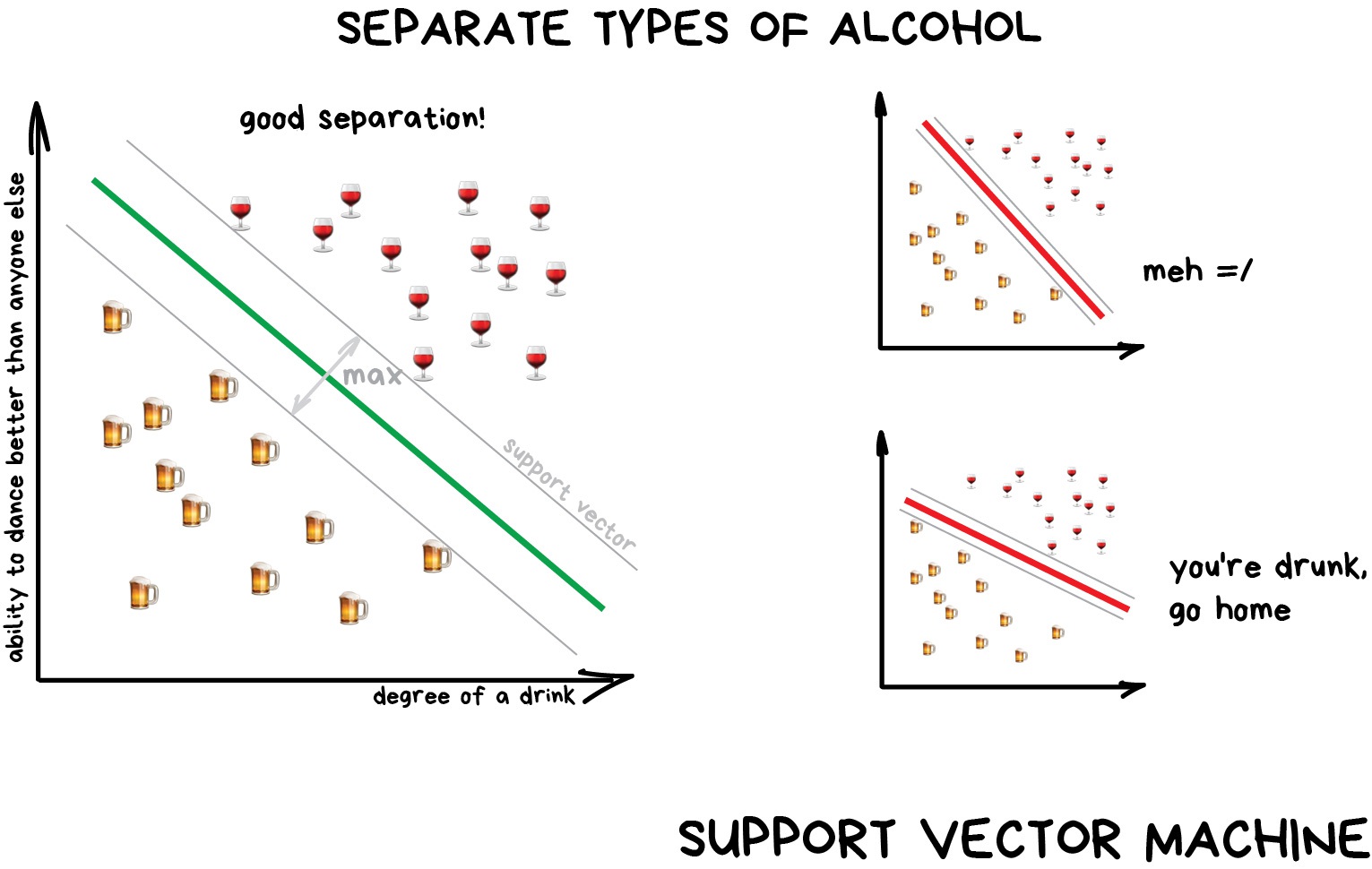

Support Vector Machines (SVM) is rightfully the most popular method of classical classification. It was used to classify everything in existence: plants by appearance in photos, documents by categories, etc.

The idea behind SVM is simple–it's trying to draw two lines between your data points with the largest margin between them. Look at the picture:

There's one very useful side of the classification—anomaly detection. When a feature does not fit any of the classes, we highlight it. Now that's used in medicine—on MRIs, computers highlight all the suspicious areas or deviations of the test. Stock markets use it to detect abnormal behaviour of traders to find the insiders. When teaching the computer the right things, we automatically teach it what things are wrong.

Today, neural networks are more frequently used for classification. Well, that's what they were created for.

The rule of thumb is the more complex the data, the more complex the algorithm. For text, numbers, and tables, I'd choose the classical approach. The models are smaller there, they learn faster and work more clearly. For pictures, video and all other complicated big data things, I'd definitely look at neural networks.

Just five years ago you could find a face classifier built on SVM. Today it's easier to choose from hundreds of pre-trained networks. Nothing has changed for spam filters, though. They are still written with SVM. And there's no good reason to switch from it anywhere.

Even my website has SVM-based spam detection in comments ¯_(ツ)_/¯

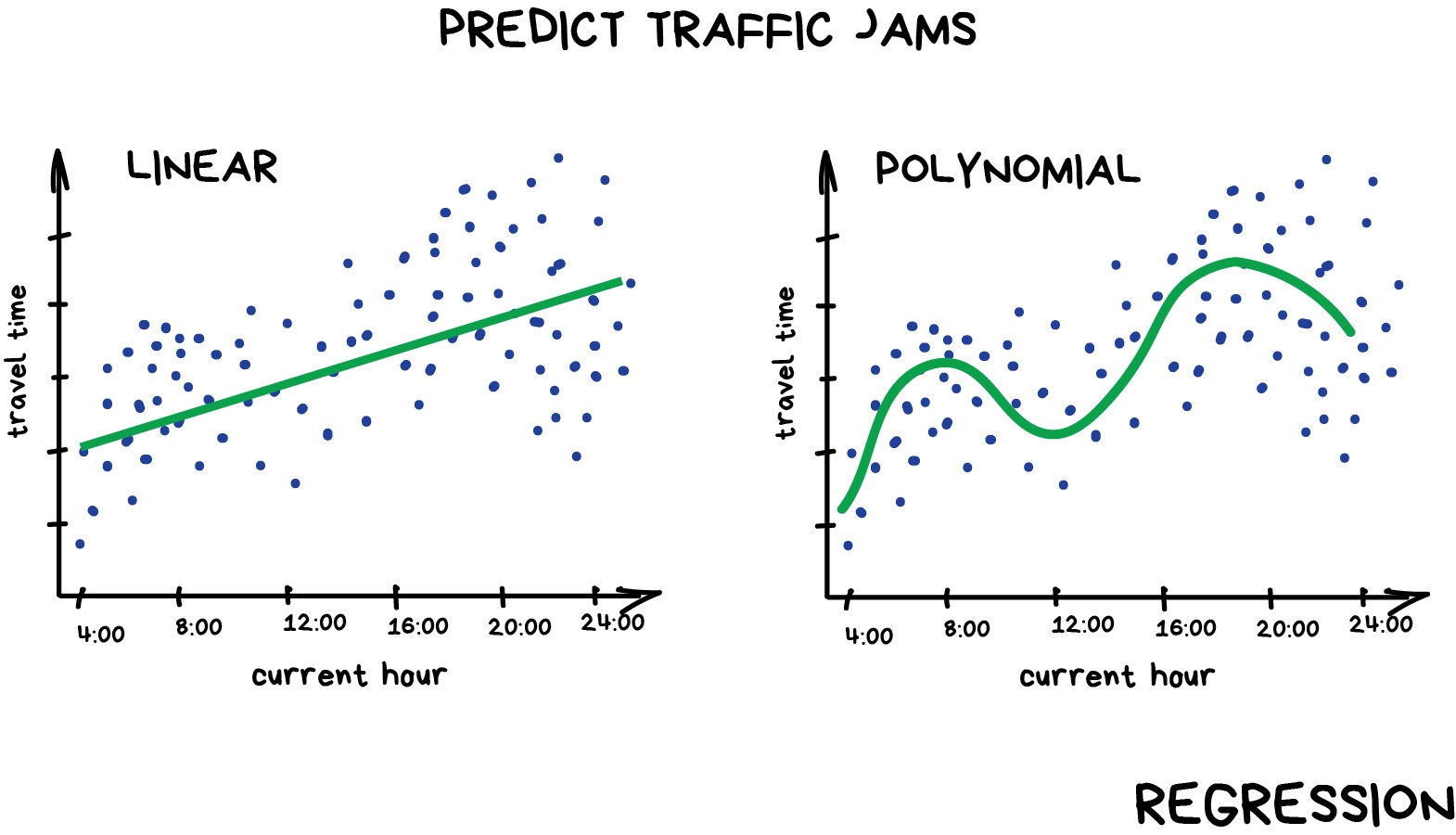

"Draw a line through these dots. Yep, that's the machine learning"

Today this is used for:

- Stock price forecasts

- Demand and sales volume analysis

- Medical diagnosis

- Any number-time correlations

Popular algorithms are Linear and Polynomial regressions.

Regression is basically classification where we forecast a number instead of category. Examples are car price by its mileage, traffic by time of the day, demand volume by growth of the company etc. Regression is perfect when something depends on time.

Everyone who works with finance and analysis loves regression. It's even built-in to Excel. And it's super smooth inside—the machine simply tries to draw a line that indicates average correlation. Though, unlike a person with a pen and a whiteboard, machine does so with mathematical accuracy, calculating the average interval to every dot.

When the line is straight—it's a linear regression, when it's curved–polynomial. These are two major types of regression. The other ones are more exotic. Logistic regression is a black sheep in the flock. Don't let it trick you, as it's a classification method, not regression.

It's okay to mess with regression and classification, though. Many classifiers turn into regression after some tuning. We can not only define the class of the object but memorize how close it is. Here comes a regression.

If you want to get deeper into this, check these series: Machine Learning for Humans. I really love and recommend it!

Unsupervised was invented a bit later, in the '90s. It is used less often, but sometimes we simply have no choice.

Labeled data is luxury. But what if I want to create, let's say, a bus classifier? Should I manually take photos of million fucking buses on the streets and label each of them? No way, that will take a lifetime, and I still have so many games not played on my Steam account.

There's a little hope for capitalism in this case. Thanks to social stratification, we have millions of cheap workers and services like Mechanical Turk who are ready to complete your task for $0.05. And that's how things usually get done here.

Or you can try to use unsupervised learning. But I can't remember any good practical application for it, though. It's usually useful for exploratory data analysis but not as the main algorithm. Specially trained meatbag with Oxford degree feeds the machine with a ton of garbage and watches it. Are there any clusters? No. Any visible relations? No. Well, continue then. You wanted to work in data science, right?

"Divides objects based on unknown features. Machine chooses the best way"

Nowadays used:

- For market segmentation (types of customers, loyalty)

- To merge close points on a map

- For image compression

- To analyze and label new data

- To detect abnormal behavior

Popular algorithms: K-means_clustering, Mean-Shift, DBSCAN

Clustering is a classification with no predefined classes. It’s like dividing socks by color when you don't remember all the colors you have. Clustering algorithm trying to find similar (by some features) objects and merge them in a cluster. Those who have lots of similar features are joined in one class. With some algorithms, you even can specify the exact number of clusters you want.

An excellent example of clustering—markers on web maps. When you're looking for all vegan restaurants around, the clustering engine groups them to blobs with a number. Otherwise, your browser would freeze, trying to draw all three million vegan restaurants in that hipster downtown.

Apple Photos and Google Photos use more complex clustering. They're looking for faces in photos to create albums of your friends. The app doesn't know how many friends you have and how they look, but it's trying to find the common facial features. Typical clustering.

Another popular issue is image compression. When saving the image to PNG you can set the palette, let's say, to 32 colors. It means clustering will find all the "reddish" pixels, calculate the "average red" and set it for all the red pixels. Fewer colors—lower file size—profit!

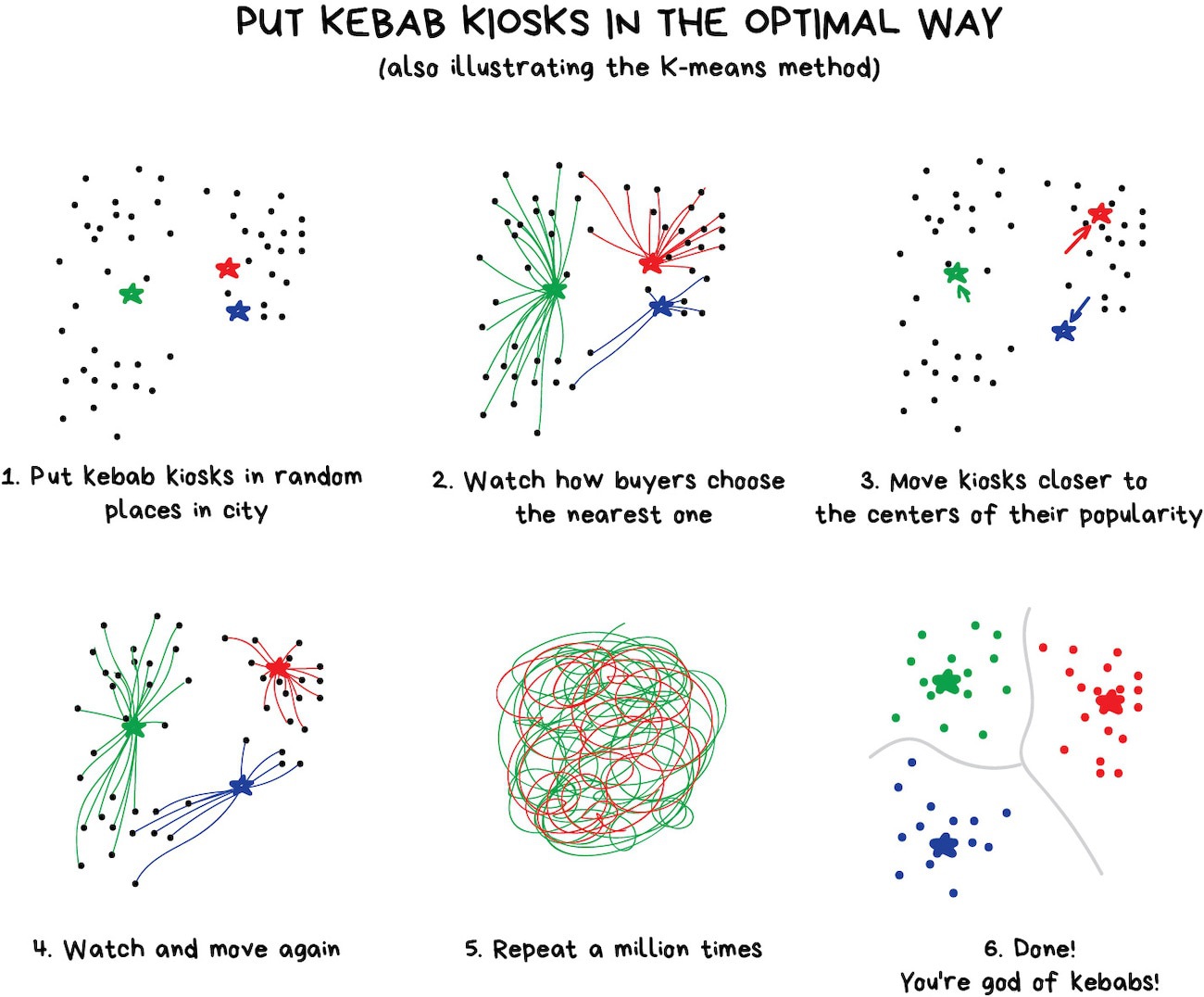

However, you may have problems with colors like Cyan◼︎-like colors. Is it green or blue? Here comes the K-Means algorithm.

It randomly sets 32 color dots in the palette. Now, those are centroids. The remaining points are marked as assigned to the nearest centroid. Thus, we get kind of galaxies around these 32 colors. Then we're moving the centroid to the center of its galaxy and repeat that until centroids stop moving.

All done. Clusters defined, stable, and there are exactly 32 of them. Here is a more real-world explanation:

Searching for the centroids is convenient. Though, in real life clusters not always circles. Let's imagine you're a geologist. And you need to find some similar minerals on the map. In that case, the clusters can be weirdly shaped and even nested. Also, you don't even know how many of them to expect. 10? 100?

K-means does not fit here, but DBSCAN can be helpful. Let's say, our dots are people at the town square. Find any three people standing close to each other and ask them to hold hands. Then, tell them to start grabbing hands of those neighbors they can reach. And so on, and so on until no one else can take anyone's hand. That's our first cluster. Repeat the process until everyone is clustered. Done.

A nice bonus: a person who has no one to hold hands with—is an anomaly.

It all looks cool in motion:

Just like classification, clustering could be used to detect anomalies. User behaves abnormally after signing up? Let the machine ban him temporarily and create a ticket for the support to check it. Maybe it's a bot. We don't even need to know what "normal behavior" is, we just upload all user actions to our model and let the machine decide if it's a "typical" user or not.

This approach doesn't work that well compared to the classification one, but it never hurts to try.

"Assembles specific features into more high-level ones"

Nowadays is used for:

- Recommender systems (★)

- Beautiful visualizations

- Topic modeling and similar document search

- Fake image analysis

- Risk management

Popular algorithms: Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Singular Value Decomposition (SVD), Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA), Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA, pLSA, GLSA), t-SNE (for visualization)

Previously these methods were used by hardcore data scientists, who had to find "something interesting" in huge piles of numbers. When Excel charts didn't help, they forced machines to do the pattern-finding. That's how they got Dimension Reduction or Feature Learning methods.

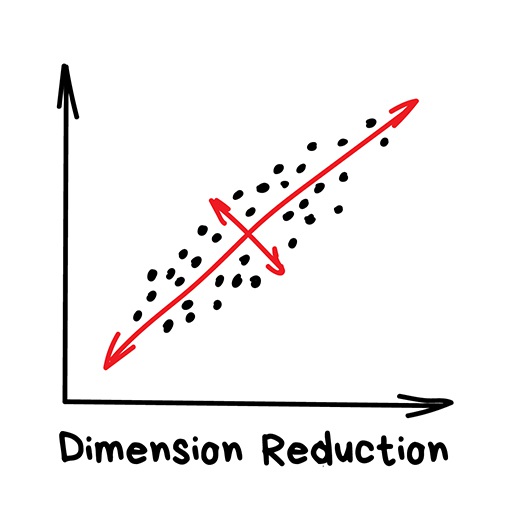

Projecting 2D-data to a line (PCA)

It is always more convenient for people to use abstractions, not a bunch of fragmented features. For example, we can merge all dogs with triangle ears, long noses, and big tails to a nice abstraction—"shepherd". Yes, we're losing some information about the specific shepherds, but the new abstraction is much more useful for naming and explaining purposes. As a bonus, such "abstracted" models learn faster, overfit less and use a lower number of features.

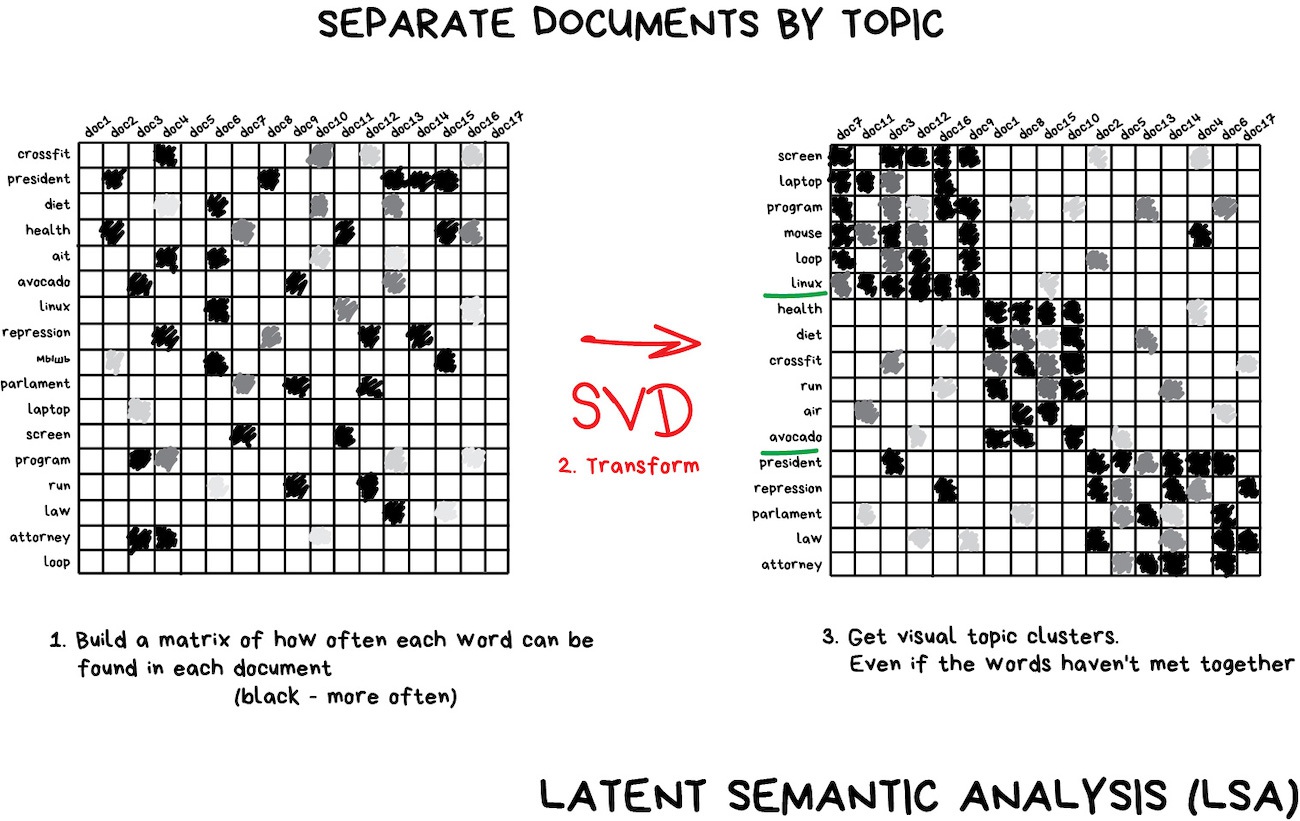

These algorithms became an amazing tool for Topic Modeling. We can abstract from specific words to their meanings. This is what Latent semantic analysis (LSA) does. It is based on how frequently you see the word on the exact topic. Like, there are more tech terms in tech articles, for sure. The names of politicians are mostly found in political news, etc.

Yes, we can just make clusters from all the words at the articles, but we will lose all the important connections (for example the same meaning of battery and accumulator in different documents). LSA will handle it properly, that's why its called "latent semantic".

So we need to connect the words and documents into one feature to keep these latent connections—it turns out that Singular decomposition (SVD) nails this task, revealing useful topic clusters from seen-together words.

Recommender Systems and Collaborative Filtering is another super-popular use of the dimensionality reduction method. Seems like if you use it to abstract user ratings, you get a great system to recommend movies, music, games and whatever you want.

It's barely possible to fully understand this machine abstraction, but it's possible to see some correlations on a closer look. Some of them correlate with user's age—kids play Minecraft and watch cartoons more; others correlate with movie genre or user hobbies.

Machines get these high-level concepts even without understanding them, based only on knowledge of user ratings. Nicely done, Mr.Computer. Now we can write a thesis on why bearded lumberjacks love My Little Pony.

"Look for patterns in the orders' stream"

Nowadays is used:

- To forecast sales and discounts

- To analyze goods bought together

- To place the products on the shelves

- To analyze web surfing patterns

Popular algorithms: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Association_rule_learning#Algorithms

This includes all the methods to analyze shopping carts, automate marketing strategy, and other event-related tasks. When you have a sequence of something and want to find patterns in it—try these thingys.

Say, a customer takes a six-pack of beers and goes to the checkout. Should we place peanuts on the way? How often do people buy them together? Yes, it probably works for beer and peanuts, but what other sequences can we predict? Can a small change in the arrangement of goods lead to a significant increase in profits?

Same goes for e-commerce. The task is even more interesting there—what is the customer going to buy next time?

No idea why rule-learning seems to be the least elaborated upon category of machine learning. Classical methods are based on a head-on look through all the bought goods using trees or sets. Algorithms can only search for patterns, but cannot generalize or reproduce those on new examples.

In the real world, every big retailer builds their own proprietary solution, so nooo revolutions here for you. The highest level of tech here—recommender systems. Though, I may be not aware of a breakthrough in the area. Let me know in the comments if you have something to share.

"Throw a robot into a maze and let it find an exit"

Nowadays used for:

- Self-driving cars

- Robot vacuums

- Games

- Automating trading

- Enterprise resource management

Popular algorithms: Q-Learning, SARSA, DQN, A3C, Genetic algorithm

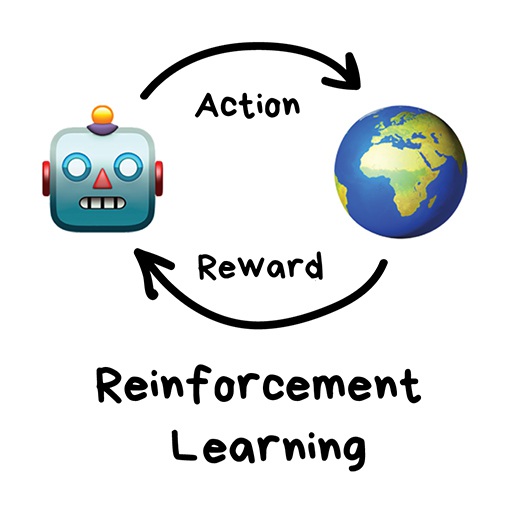

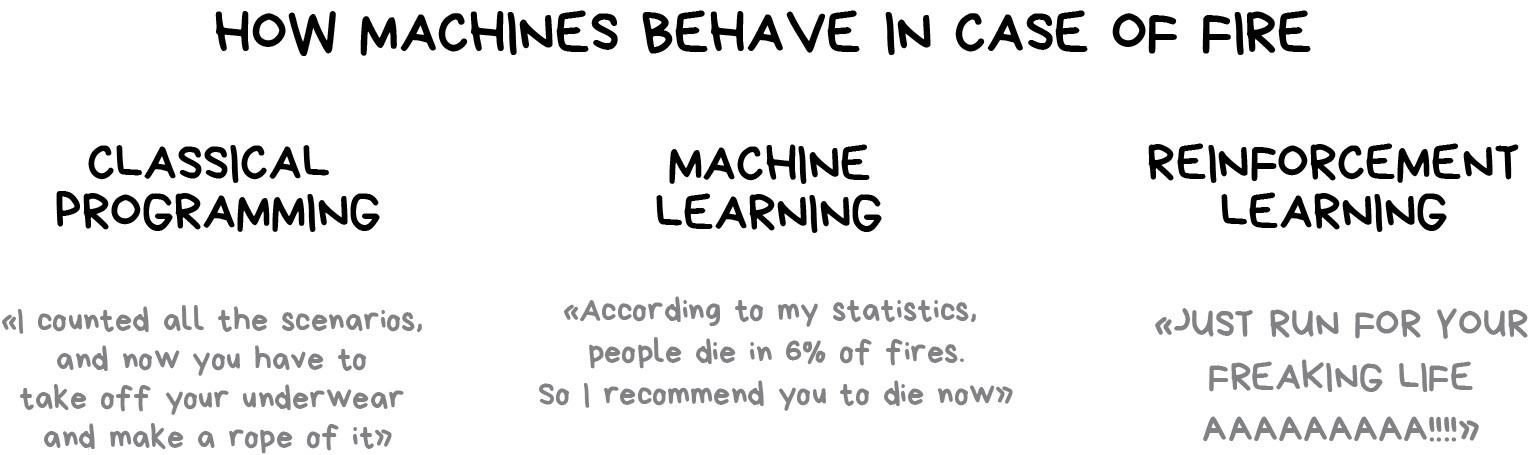

Finally, we get to something looks like real artificial intelligence. In lots of articles reinforcement learning is placed somewhere in between of supervised and unsupervised learning. They have nothing in common! Is this because of the name?

Reinforcement learning is used in cases when your problem is not related to data at all, but you have an environment to live in. Like a video game world or a city for self-driving car.

Neural network plays Mario

Knowledge of all the road rules in the world will not teach the autopilot how to drive on the roads. Regardless of how much data we collect, we still can't foresee all the possible situations. This is why its goal is to minimize error, not to predict all the moves.

Surviving in an environment is a core idea of reinforcement learning. Throw poor little robot into real life, punish it for errors and reward it for right deeds. Same way we teach our kids, right?

More effective way here—to build a virtual city and let self-driving car to learn all its tricks there first. That's exactly how we train auto-pilots right now. Create a virtual city based on a real map, populate with pedestrians and let the car learn to kill as few people as possible. When the robot is reasonably confident in this artificial GTA, it's freed to test in the real streets. Fun!

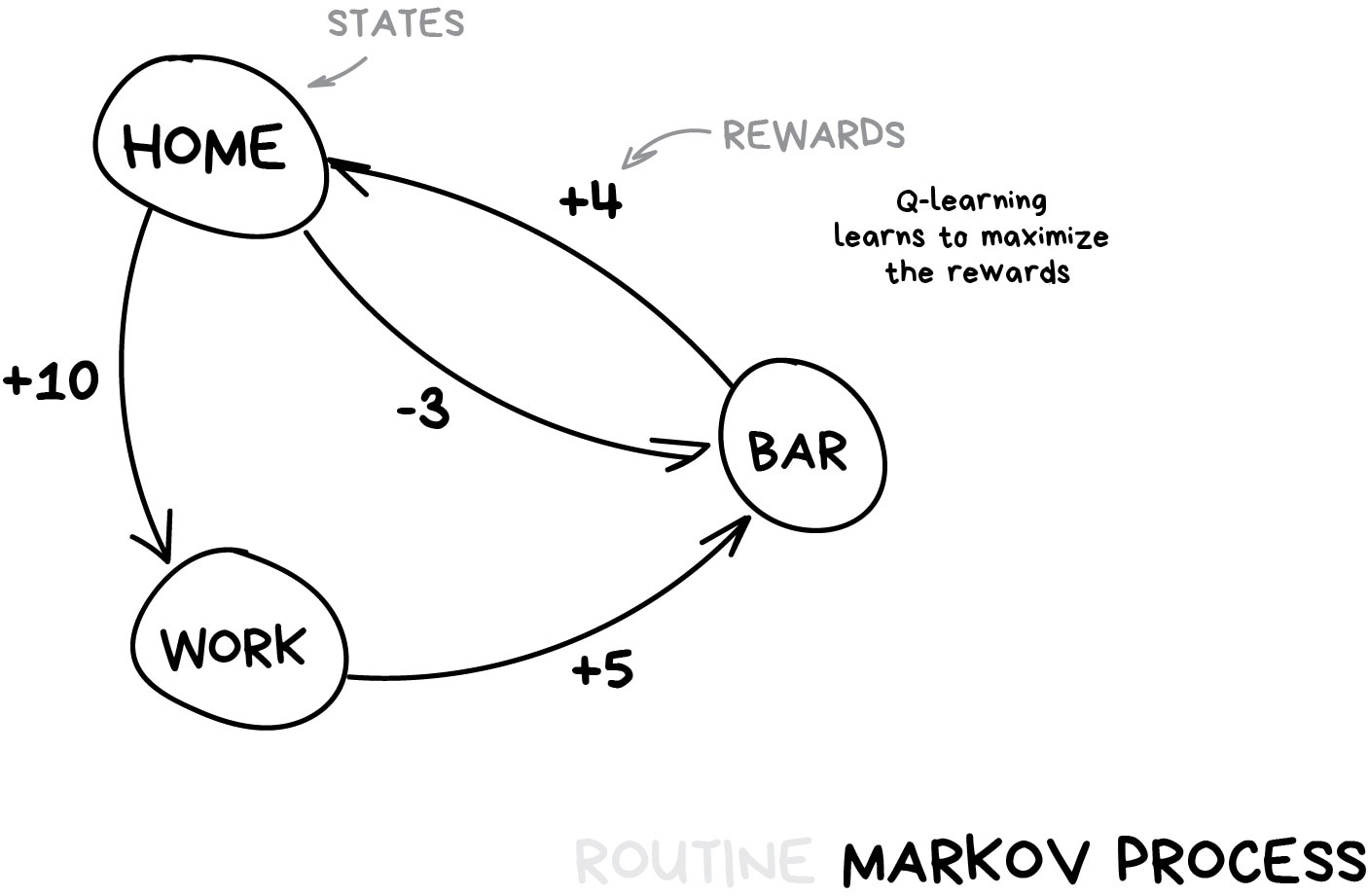

There may be two different approaches—Model-Based and Model-Free.

Model-Based means that car needs to memorize a map or its parts. That's a pretty outdated approach since it's impossible for the poor self-driving car to memorize the whole planet.

In Model-Free learning, the car doesn't memorize every movement but tries to generalize situations and act rationally while obtaining a maximum reward.

Remember the news about AI beating a top player at the game of Go? Despite shortly before this it being proved that the number of combinations in this game is greater than the number of atoms in the universe.

This means the machine could not remember all the combinations and thereby win Go (as it did chess). At each turn, it simply chose the best move for each situation, and it did well enough to outplay a human meatbag.

This approach is a core concept behind Q-learning and its derivatives (SARSA & DQN). 'Q' in the name stands for "Quality" as a robot learns to perform the most "qualitative" action in each situation and all the situations are memorized as a simple markovian process.

Such a machine can test billions of situations in a virtual environment, remembering which solutions led to greater reward. But how can it distinguish previously seen situations from a completely new one? If a self-driving car is at a road crossing and the traffic light turns green—does it mean it can go now? What if there's an ambulance rushing through a street nearby?

The answer today is "no one knows". There's no easy answer. Researchers are constantly searching for it but meanwhile only finding workarounds. Some would hardcode all the situations manually that let them solve exceptional cases, like the trolley problem. Others would go deep and let neural networks do the job of figuring it out. This led us to the evolution of Q-learning called Deep Q-Network (DQN). But they are not a silver bullet either.

Reinforcement Learning for an average person would look like a real artificial intelligence. Because it makes you think wow, this machine is making decisions in real life situations! This topic is hyped right now, it's advancing with incredible pace and intersecting with a neural network to clean your floor more accurately. Amazing world of technologies!

Off-topic. When I was a student, genetic algorithms (link has cool visualization) were really popular. This is about throwing a bunch of robots into a single environment and making them try reaching the goal until they die. Then we pick the best ones, cross them, mutate some genes and rerun the simulation. After a few milliard years, we will get an intelligent creature. Probably. Evolution at its finest.

Genetic algorithms are considered as part of reinforcement learning and they have the most important feature proved by decade-long practice: no one gives a shit about them.

Humanity still couldn't come up with a task where those would be more effective than other methods. But they are great for student experiments and let people get their university supervisors excited about "artificial intelligence" without too much labour. And youtube would love it as well.

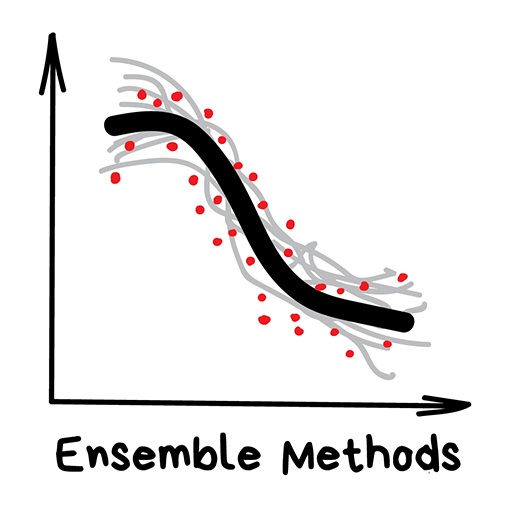

"Bunch of stupid trees learning to correct errors of each other"

Nowadays is used for:

- Everything that fits classical algorithm approaches (but works better)

- Search systems (★)

- Computer vision

- Object detection

Popular algorithms: Random Forest, Gradient Boosting

It's time for modern, grown-up methods. Ensembles and neural networks are two main fighters paving our path to a singularity. Today they are producing the most accurate results and are widely used in production.

However, the neural networks got all the hype today, while the words like "boosting" or "bagging" are scarce hipsters on TechCrunch.

Despite all the effectiveness the idea behind these is overly simple. If you take a bunch of inefficient algorithms and force them to correct each other's mistakes, the overall quality of a system will be higher than even the best individual algorithms.

You'll get even better results if you take the most unstable algorithms that are predicting completely different results on small noise in input data. Like Regression and Decision Trees. These algorithms are so sensitive to even a single outlier in input data to have models go mad.

In fact, this is what we need.

We can use any algorithm we know to create an ensemble. Just throw a bunch of classifiers, spice it up with regression and don't forget to measure accuracy. From my experience: don't even try a Bayes or kNN here. Although "dumb", they are really stable. That's boring and predictable. Like your ex.

Instead, there are three battle-tested methods to create ensembles.

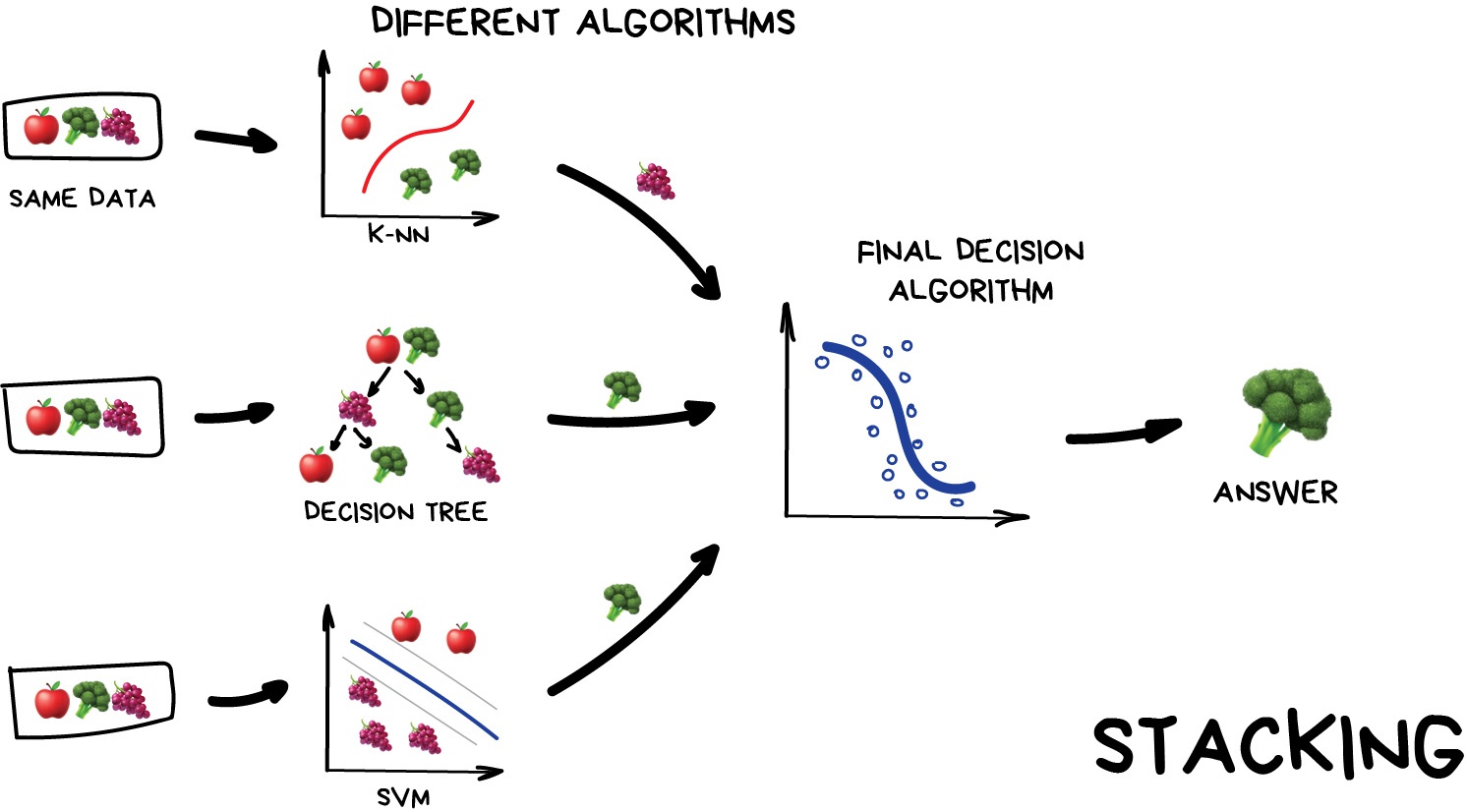

Stacking Output of several parallel models is passed as input to the last one which makes a final decision. Like that girl who asks her girlfriends whether to meet with you in order to make the final decision herself.

Emphasis here on the word "different". Mixing the same algorithms on the same data would make no sense. The choice of algorithms is completely up to you. However, for final decision-making model, regression is usually a good choice.

Based on my experience stacking is less popular in practice, because two other methods are giving better accuracy.

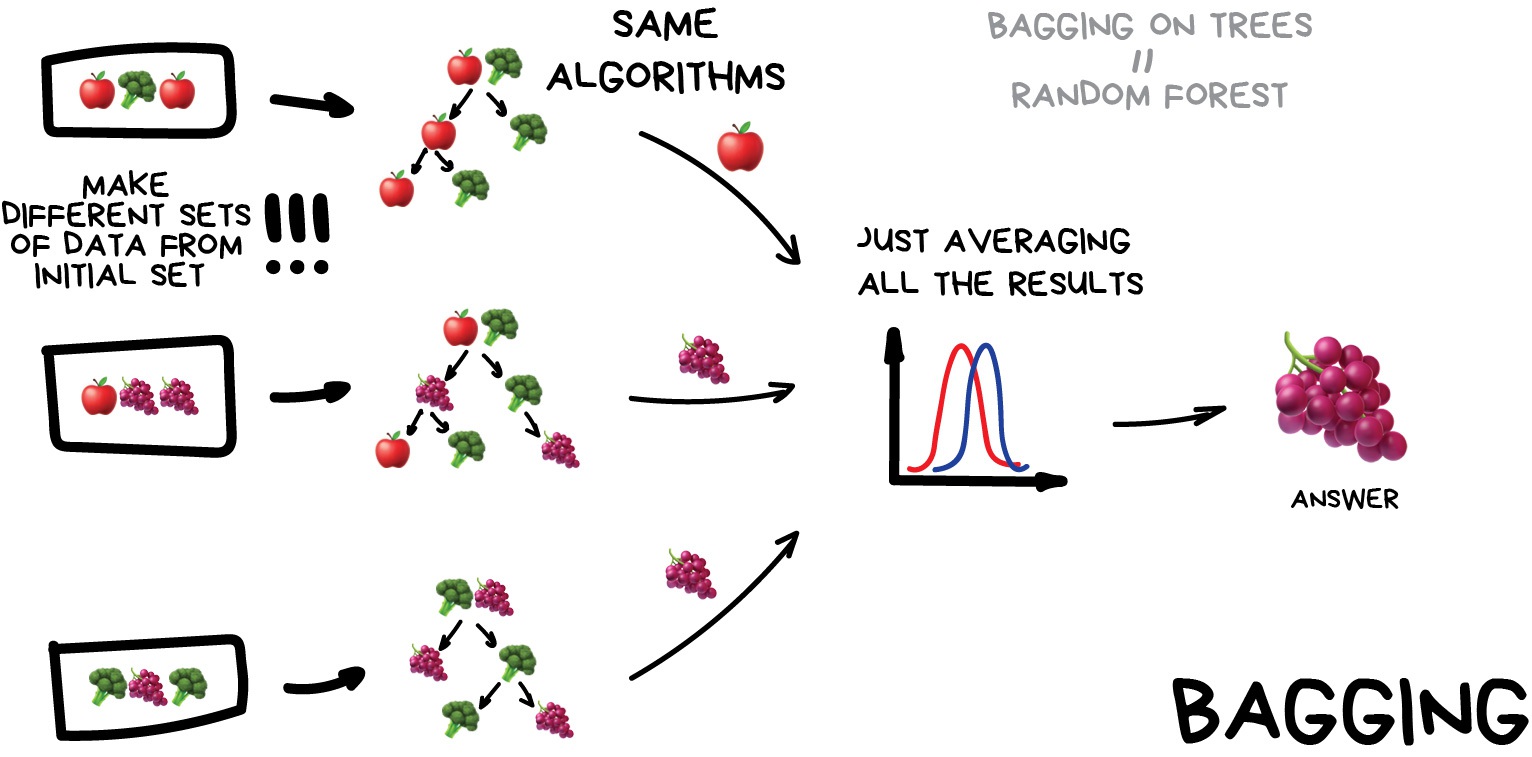

Bagging aka Bootstrap AGGregatING. Use the same algorithm but train it on different subsets of original data. In the end—just average answers.

Data in random subsets may repeat. For example, from a set like "1-2-3" we can get subsets like "2-2-3", "1-2-2", "3-1-2" and so on. We use these new datasets to teach the same algorithm several times and then predict the final answer via simple majority voting.

The most famous example of bagging is the Random Forest algorithm, which is simply bagging on the decision trees (which were illustrated above). When you open your phone's camera app and see it drawing boxes around people's faces—it's probably the results of Random Forest work. Neural networks would be too slow to run real-time yet bagging is ideal given it can calculate trees on all the shaders of a video card or on these new fancy ML processors.

In some tasks, the ability of the Random Forest to run in parallel is more important than a small loss in accuracy to the boosting, for example. Especially in real-time processing. There is always a trade-off.

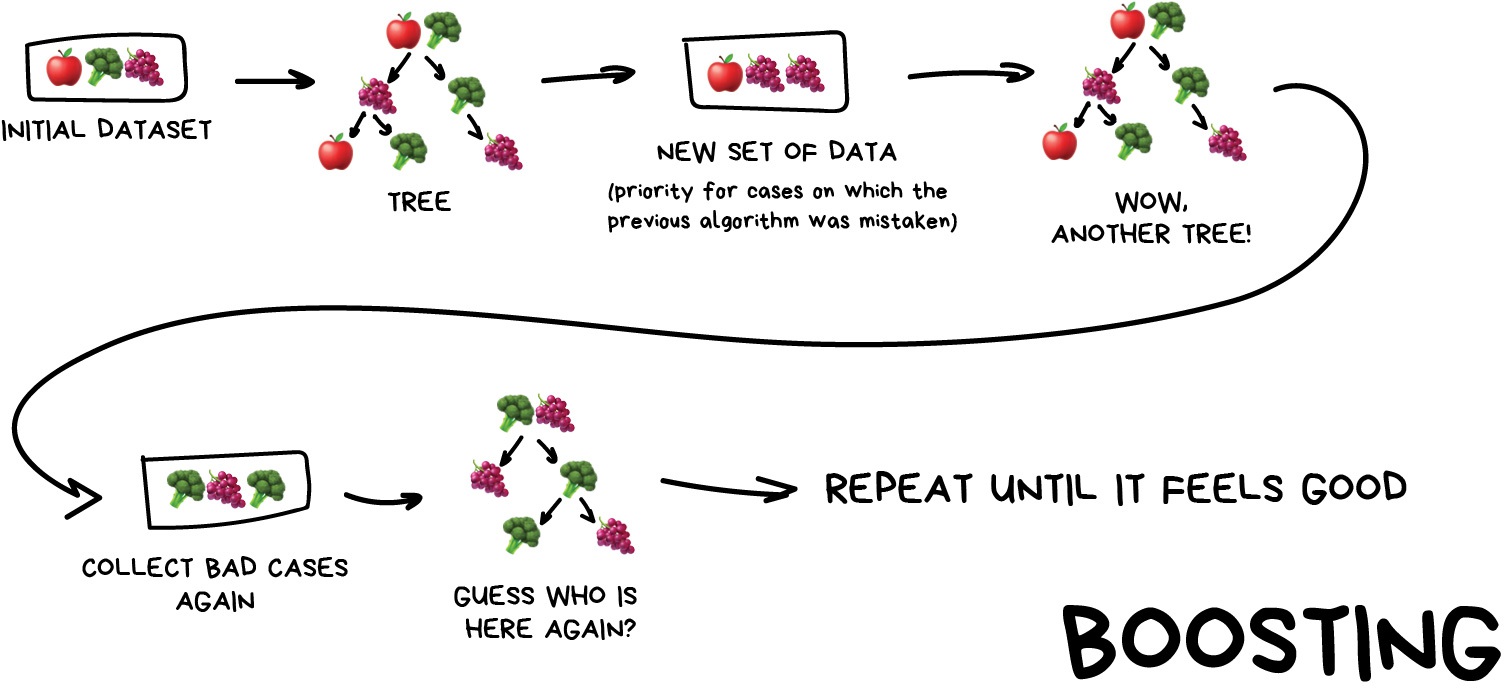

Boosting Algorithms are trained one by one sequentially. Each subsequent one paying most of its attention to data points that were mispredicted by the previous one. Repeat until you are happy.

Same as in bagging, we use subsets of our data but this time they are not randomly generated. Now, in each subsample we take a part of the data the previous algorithm failed to process. Thus, we make a new algorithm learn to fix the errors of the previous one.

The main advantage here—a very high, even illegal in some countries precision of classification that all cool kids can envy. The cons were already called out—it doesn't parallelize. But it's still faster than neural networks. It's like a race between a dump truck and a racecar. The truck can do more, but if you want to go fast—take a car.

If you want a real example of boosting—open Facebook or Google and start typing in a search query. Can you hear an army of trees roaring and smashing together to sort results by relevancy? That's because they are using boosting.

"We have a thousand-layer network, dozens of video cards, but still no idea where to use it. Let's generate cat pics!"

Used today for:

- Replacement of all algorithms above

- Object identification on photos and videos

- Speech recognition and synthesis

- Image processing, style transfer

- Machine translation

Popular architectures: Perceptron, Convolutional Network (CNN), Recurrent Networks (RNN), Autoencoders

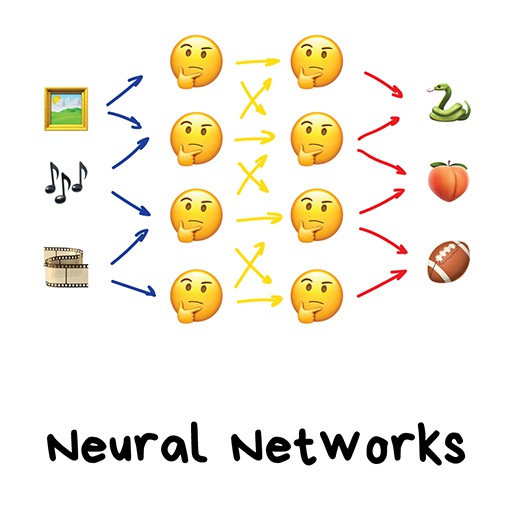

If no one has ever tried to explain neural networks to you using "human brain" analogies, you're happy. Tell me your secret. But first, let me explain it the way I like.

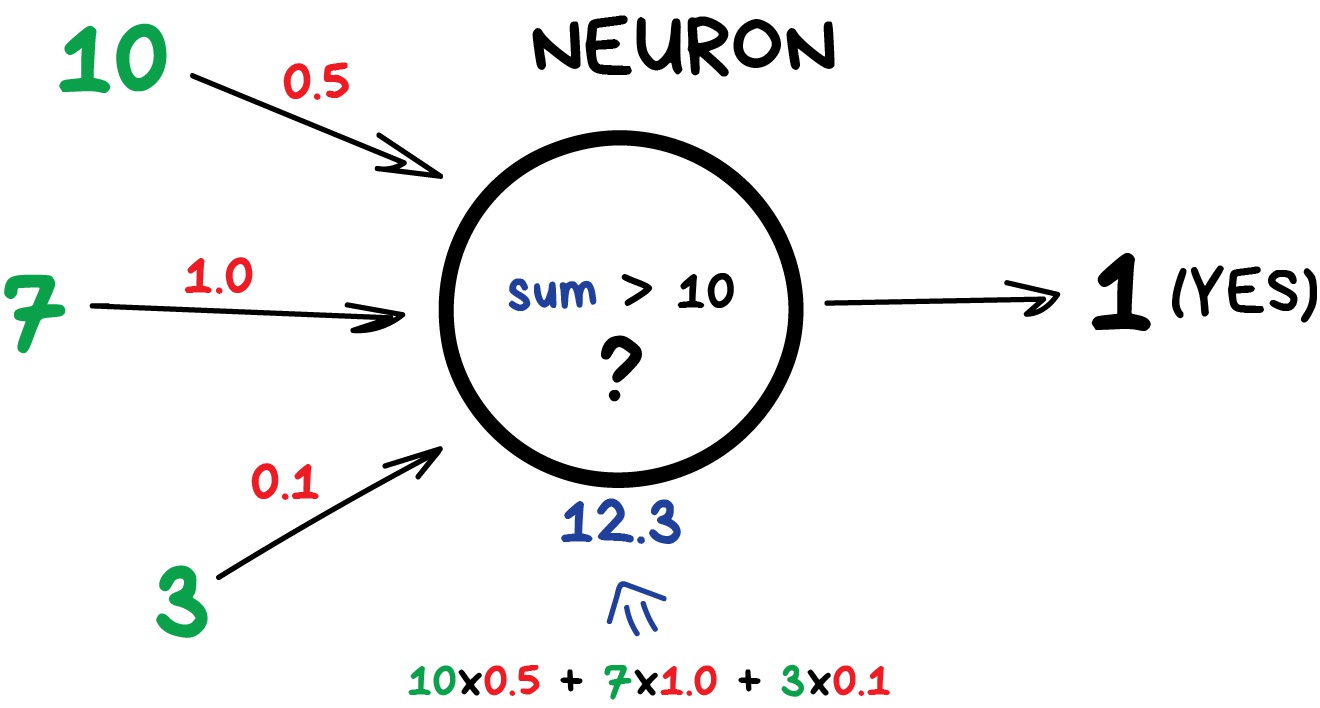

Any neural network is basically a collection of neurons and connections between them. Neuron is a function with a bunch of inputs and one output. Its task is to take all numbers from its input, perform a function on them and send the result to the output.

Here is an example of a simple but useful in real life neuron: sum up all numbers from the inputs and if that sum is bigger than N—give 1 as a result. Otherwise—zero.

Connections are like channels between neurons. They connect outputs of one neuron with the inputs of another so they can send digits to each other. Each connection has only one parameter—weight. It's like a connection strength for a signal. When the number 10 passes through a connection with a weight 0.5 it turns into 5.

These weights tell the neuron to respond more to one input and less to another. Weights are adjusted when training—that's how the network learns. Basically, that's all there is to it.

To prevent the network from falling into anarchy, the neurons are linked by layers, not randomly. Within a layer neurons are not connected, but they are connected to neurons of the next and previous layers. Data in the network goes strictly in one direction—from the inputs of the first layer to the outputs of the last.

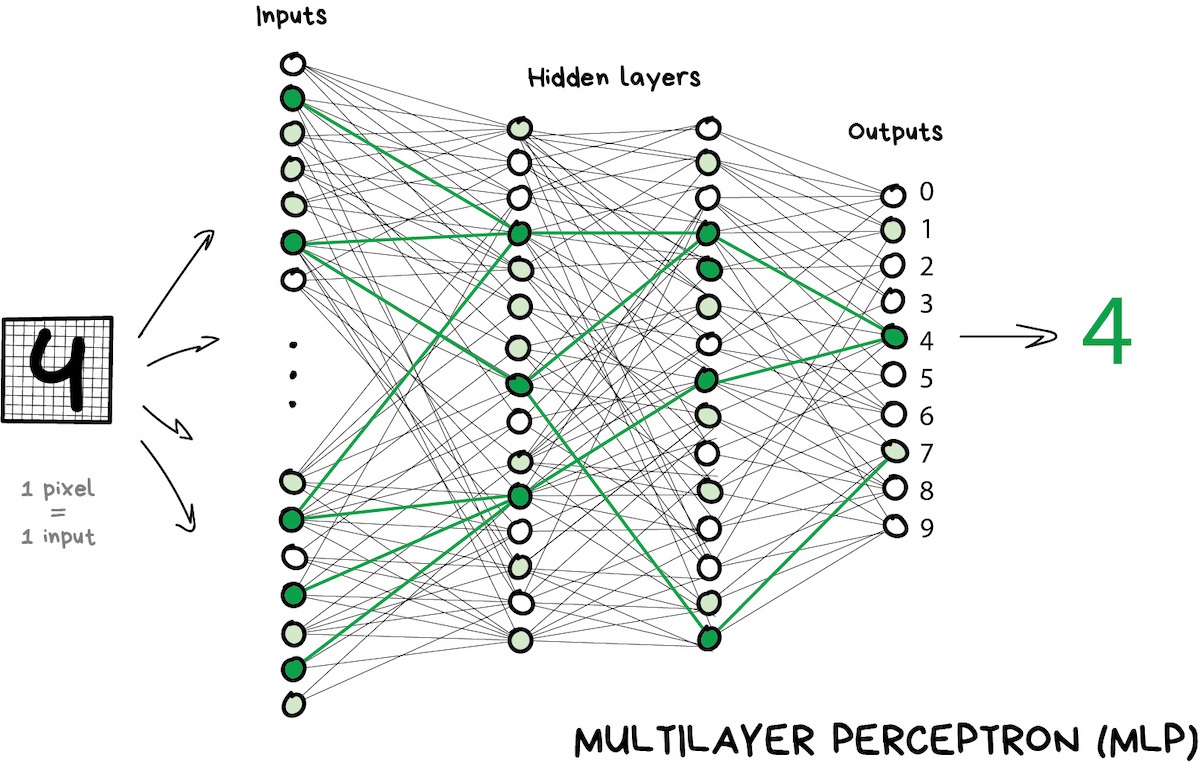

If you throw in a sufficient number of layers and put the weights correctly, you will get the following: by applying to the input, say, the image of handwritten digit 4, black pixels activate the associated neurons, they activate the next layers, and so on and on, until it finally lights up the exit in charge of the four. The result is achieved.

When doing real-life programming nobody is writing neurons and connections. Instead, everything is represented as matrices and calculated based on matrix multiplication for better performance. My favourite video on this and its sequel below describe the whole process in an easily digestible way using the example of recognizing hand-written digits. Watch them if you want to figure this out.

A network that has multiple layers that have connections between every neuron is called a perceptron (MLP) and considered the simplest architecture for a novice. I didn't see it used for solving tasks in production.

After we constructed a network, our task is to assign proper ways so neurons will react correctly to incoming signals. Now is the time to remember that we have data that is samples of 'inputs' and proper 'outputs'. We will be showing our network a drawing of the same digit 4 and tell it 'adapt your weights so whenever you see this input your output would emit 4'.

To start with, all weights are assigned randomly. After we show it a digit it emits a random answer because the weights are not correct yet, and we compare how much this result differs from the right one. Then we start traversing network backward from outputs to inputs and tell every neuron 'hey, you did activate here but you did a terrible job and everything went south from here downwards, let's keep less attention to this connection and more of that one, mkay?'.

After hundreds of thousands of such cycles of 'infer-check-punish', there is a hope that the weights are corrected and act as intended. The science name for this approach is Backpropagation, or a 'method of backpropagating an error'. Funny thing it took twenty years to come up with this method. Before this we still taught neural networks somehow.

My second favorite vid is describing this process in depth, but it's still very accessible.

A well trained neural network can fake the work of any of the algorithms described in this chapter (and frequently works more precisely). This universality is what made them widely popular. Finally we have an architecture of human brain they said we just need to assemble lots of layers and teach them on any possible data they hoped. Then the first AI winter started, then it thawed, and then another wave of disappointment hit.

It turned out networks with a large number of layers required computation power unimaginable at that time. Nowadays any gamer PC with geforces outperforms the datacenters of that time. So people didn't have any hope then to acquire computation power like that and neural networks were a huge bummer.

And then ten years ago deep learning rose.

In 2012 convolutional neural networks acquired an overwhelming victory in ImageNet competition that made the world suddenly remember about methods of deep learning described in the ancient 90s. Now we have video cards!

Differences of deep learning from classical neural networks were in new methods of training that could handle bigger networks. Nowadays only theoretics would try to divide which learning to consider deep and not so deep. And we, as practitioners are using popular 'deep' libraries like Keras, TensorFlow & PyTorch even when we build a mini-network with five layers. Just because it's better suited than all the tools that came before. And we just call them neural networks.

I'll tell about two main kinds nowadays.

https://vas3k.com/blog/machine_learning/#scroll160

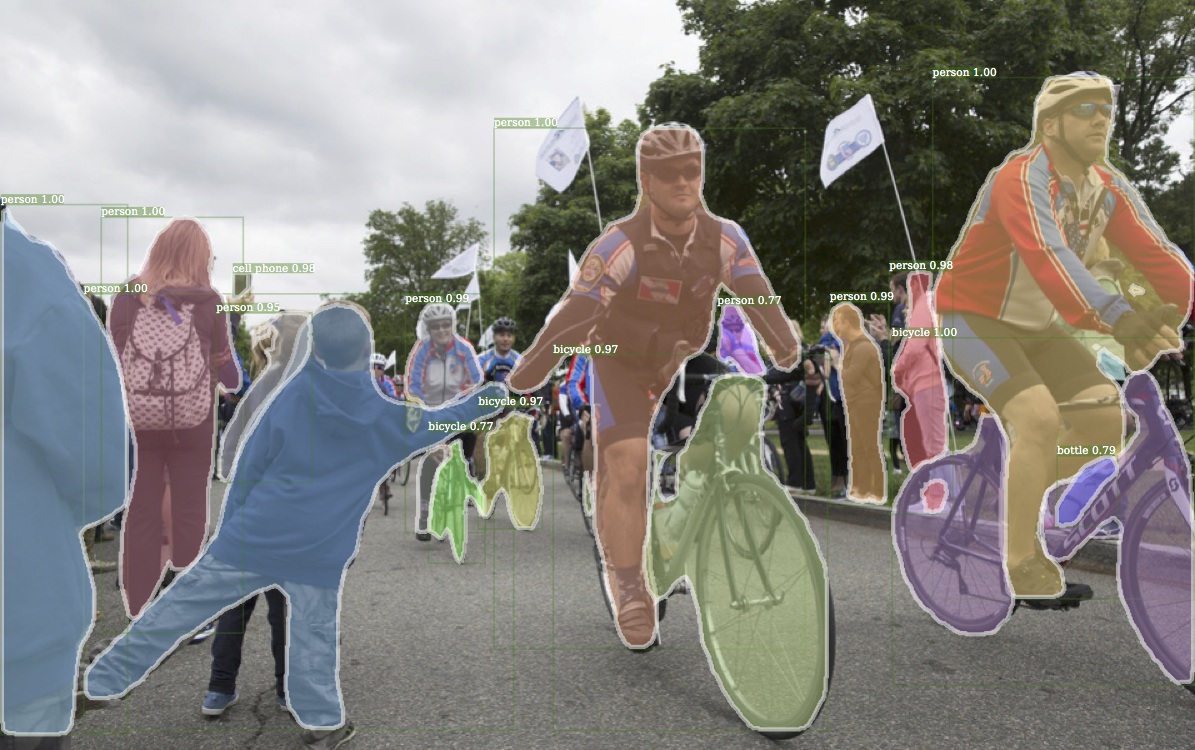

Convolutional neural networks are all the rage right now. They are used to search for objects on photos and in videos, face recognition, style transfer, generating and enhancing images, creating effects like slow-mo and improving image quality. Nowadays CNNs are used in all the cases that involve pictures and videos. Even in your iPhone several of these networks are going through your nudes to detect objects in those. If there is something to detect, heh.

Image above is a result produced by Detectron that was recently open-sourced by Facebook

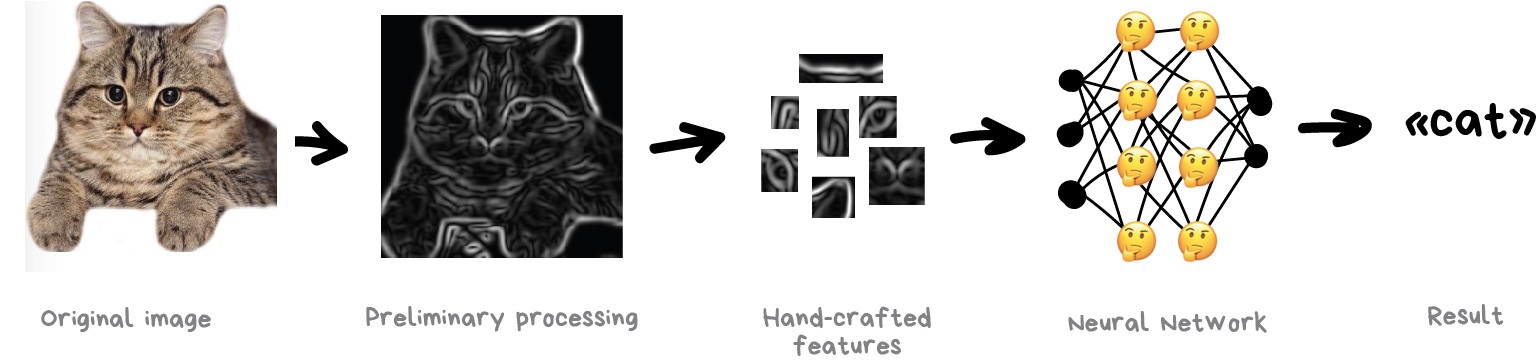

A problem with images was always the difficulty of extracting features out of them. You can split text by sentences, lookup words' attributes in specialized vocabularies, etc. But images had to be labeled manually to teach the machine where cat ears or tails were in this specific image. This approach got the name 'handcrafting features' and used to be used almost by everyone.

There are lots of issues with the handcrafting.

First of all, if a cat had its ears down or turned away from the camera: you are in trouble, the neural network won't see a thing.

Secondly, try naming on the spot 10 different features that distinguish cats from other animals. I for one couldn't do it, but when I see a black blob rushing past me at night—even if I only see it in the corner of my eye—I would definitely tell a cat from a rat. Because people don't look only at ear form or leg count and account lots of different features they don't even think about. And thus cannot explain it to the machine.

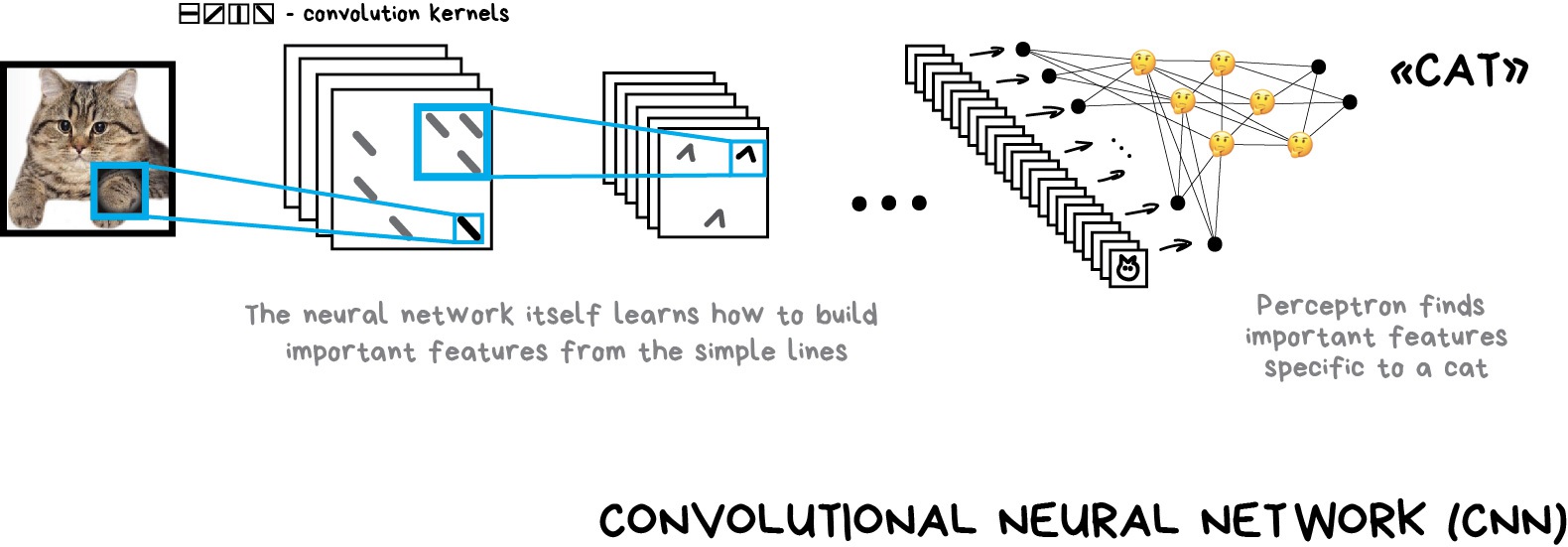

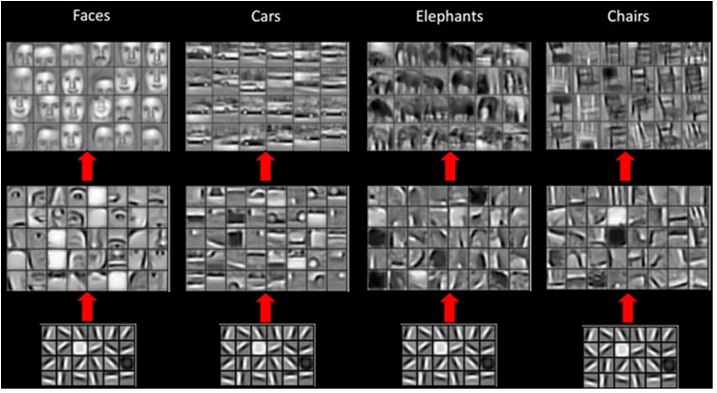

So it means the machine needs to learn such features on its own, building on top of basic lines. We'll do the following: first, we divide the whole image into 8x8 pixel blocks and assign to each a type of dominant line–either horizontal [-], vertical [|] or one of the diagonals [/]. It can also be that several would be highly visible—this happens and we are not always absolutely confident.

Output would be several tables of sticks that are in fact the simplest features representing objects edges on the image. They are images on their own but built out of sticks. So we can once again take a block of 8x8 and see how they match together. And again and again…

This operation is called convolution, which gave the name for the method. Convolution can be represented as a layer of a neural network, because each neuron can act as any function.

When we feed our neural network with lots of photos of cats it automatically assigns bigger weights to those combinations of sticks it saw the most frequently. It doesn't care whether it was a straight line of a cat's back or a geometrically complicated object like a cat's face, something will be highly activating.

As the output, we would put a simple perceptron which will look at the most activated combinations and based on that differentiate cats from dogs.

The beauty of this idea is that we have a neural net that searches for the most distinctive features of the objects on its own. We don't need to pick them manually. We can feed it any amount of images of any object just by googling billions of images with it and our net will create feature maps from sticks and learn to differentiate any object on its own.

For this I even have a handy unfunny joke:

Give your neural net a fish and it will be able to detect fish for the rest of its life. Give your neural net a fishing rod and it will be able to detect fishing rods for the rest of its life…

https://vas3k.com/blog/machine_learning/#scroll170

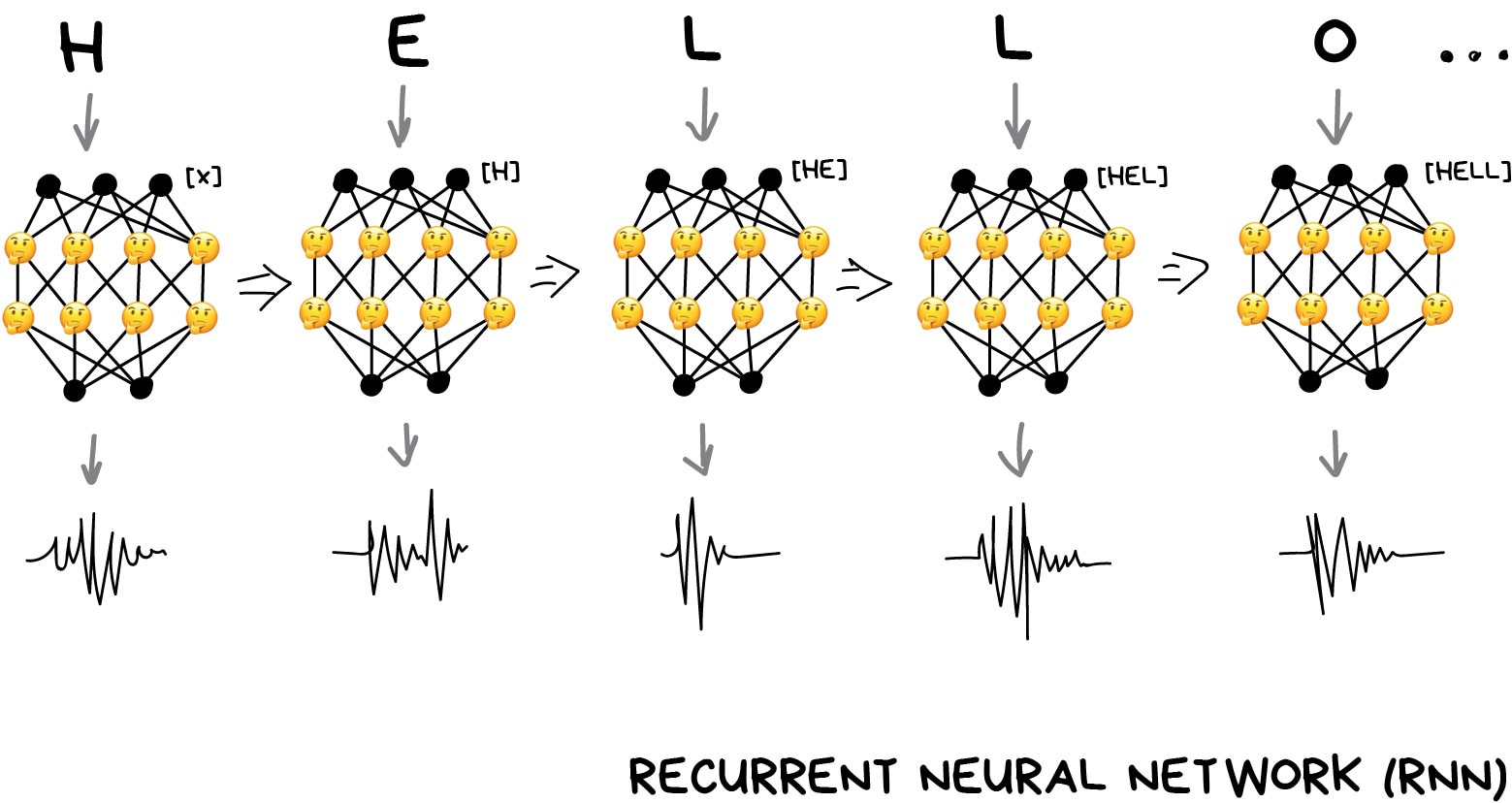

The second most popular architecture today. Recurrent networks gave us useful things like neural machine translation (here is my post about it), speech recognition and voice synthesis in smart assistants. RNNs are the best for sequential data like voice, text or music.

Remember Microsoft Sam, the old-school speech synthesizer from Windows XP? That funny guy builds words letter by letter, trying to glue them up together. Now, look at Amazon Alexa or Assistant from Google. They don't only say the words clearly, they even place the right accents!

Neural Net is trying to speak

All because modern voice assistants are trained to speak not letter by letter, but on whole phrases at once. We can take a bunch of voiced texts and train a neural network to generate an audio-sequence closest to the original speech.

In other words, we use text as input and its audio as the desired output. We ask a neural network to generate some audio for the given text, then compare it with the original, correct errors and try to get as close as possible to ideal.

Sounds like a classical learning process. Even a perceptron is suitable for this. But how should we define its outputs? Firing one particular output for each possible phrase is not an option—obviously.

Here we'll be helped by the fact that text, speech or music are sequences. They consist of consecutive units like syllables. They all sound unique but depend on previous ones. Lose this connection and you get dubstep.

We can train the perceptron to generate these unique sounds, but how will it remember previous answers? So the idea is to add memory to each neuron and use it as an additional input on the next run. A neuron could make a note for itself - hey, we had a vowel here, the next sound should sound higher (it's a very simplified example).

That's how recurrent networks appeared.

This approach had one huge problem - when all neurons remembered their past results, the number of connections in the network became so huge that it was technically impossible to adjust all the weights.

When a neural network can't forget, it can't learn new things (people have the same flaw).

The first decision was simple: limit the neuron memory. Let's say, to memorize no more than 5 recent results. But it broke the whole idea.

A much better approach came later: to use special cells, similar to computer memory. Each cell can record a number, read it or reset it. They were called long and short-term memory (LSTM) cells.

Now, when a neuron needs to set a reminder, it puts a flag in that cell. Like "it was a consonant in a word, next time use different pronunciation rules". When the flag is no longer needed, the cells are reset, leaving only the “long-term” connections of the classical perceptron. In other words, the network is trained not only to learn weights but also to set these reminders.

Simple, but it works!

CNN + RNN = Fake Obama

You can take speech samples from anywhere. BuzzFeed, for example, took Obama's speeches and trained a neural network to imitate his voice. As you see, audio synthesis is already a simple task. Video still has issues, but it's a question of time.

There are many more network architectures in the wild. I recommend a good article called Neural Network Zoo, where almost all types of neural networks are collected and briefly explained.